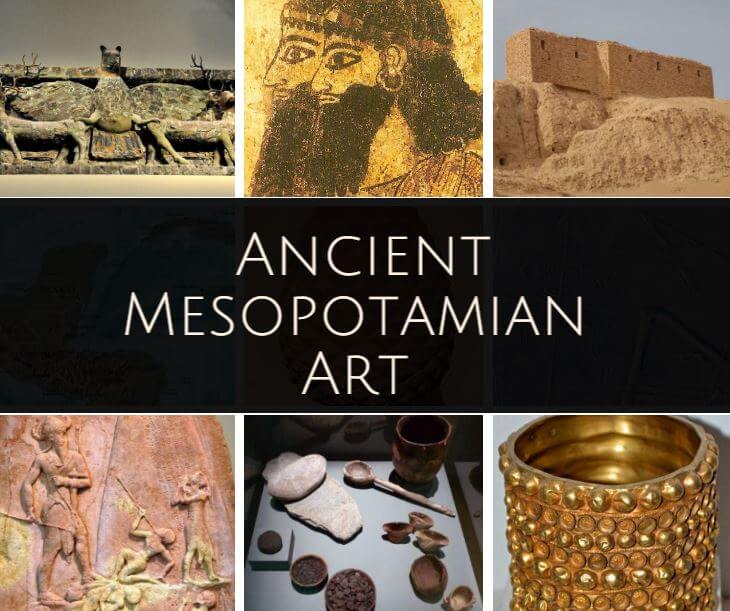

Ancient Mesopotamian art refers to the works made by the civilizations of the ancient Near East that lived in the region between the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers, modern day Iraq, from prehistory to the 6th century BC.

Ancient Mesopotamian Art

Contents

Introduction

The lowlands of Mesopotamia cover a fertile plain, but its inhabitants had to face the dangers of invasions, extreme weather, droughts, and wild animal attacks. Their art reflects both their adaptation to and fear of these natural forces, as well as their military conquests. They established urban centers in the middle of the plains, each one ruled by a temple, which was the center of commerce and religion until it was replaced in importance by the royal palace.

The Mesopotamian soil provided mud for adobes, which were this civilization’s most important constructive material. The Mesopotamians also baked this clay to get terracotta, with which they made ceramics, sculptures, and tablets to write on. Few wooden objects have been preserved. They used basalt, sandstone, diorite, and alabaster in sculptures. They also worked metals, such as bronze, copper, gold, and silver, as well as mother-of-pearl and precious stones, into finer sculptures and inlaid works. They used all kinds of stones in their cylindrical seals, like lapis lazuli, jasper, carnelian, alabaster, hematite, serpentine, and soapstone. However, some of these stones were rare in the area and had to be imported.

Mesopotamian art covers a 4000 year-long tradition that is ostensibly homogenous in terms of style and iconography. In reality, it was created and maintained by waves of ethnically and linguistically different invading peoples. Each of these groups made their own contributions to Mesopotamian art up until the Persian conquest in the 6th century BC. The Sumerians were the first people to control the region and establish their art, followed by the Akkadians, the Babylonians, and then the Assyrians. Mesopotamian political control and artistic influences spread to neighboring cultures, sometimes even reaching areas as far as the Syrian-Palestinian coast, which meant that the artistic motifs of these distant lands also influenced Mesopotamia’s urban centers. In addition to this, the rest of the peoples who invaded the region adopted Mesopotamian artistic traditions.

The Prehistoric Period

The earliest known artistic and architectural remains to date come from northern Mesopotamia, from the proto-Neolithic settlement of Qermez Dere in the Jebel Sinjar hills. Archaeological layers dating back to the 9th millennium BC have shown that there were circular huts, with one or two gypsum plastered stone pillars. In addition, when these buildings were abandoned, they placed human skulls on the ground, evidence of some ritual practice.

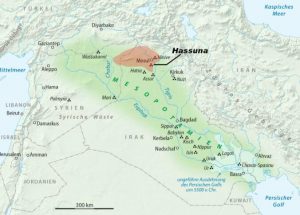

The Neolithic and Chalcolithic periods of Mesopotamian art (ca. 7000 BC – ca. 3500 BC), prior to the definitive appearance of writing, are named after corresponding archaeological sites: Hassuna, in the north, is a place where several homes and painted pottery have been found; Samarra, whose abstract and figurative ceramic designs seem to have religious significance, and Tell Halaf, a place where decorated pottery and statuettes of seated women, interpreted as goddesses of fertility, have been found. In the south, the first periods are designated as being Ubaid (ca. 5500 – ca. 4000 BC), and the ancient and middle periods are Uruk (ca. 4000 – ca. 3500 ac.). Ubaid culture is characterized by the brilliantly decorated black pottery found in the Ubaid area, although other later examples exist in Ur, Uruk, Eridu, and Uqair. One of the main features of the many archaeological levels discovered in Eridu is the existence of a small square shrine (ca. 5500 BC), rebuilt with an alcove that could house the cult statue in front of a religious altar. The later superimposed temples are more complex, with a central cella or sanctuary surrounded by small rooms with porticos. The exterior was decorated with alcoves and buttresses, typical elements in Mesopotamian temples. As for Ubaid period mud sculptures, the figure of a man in Eridu and a woman holding a child in Ur have been found.

In several of the places mentioned above, different objects pertaining to the last Uruk and Jemdet Nasr period, also known as the Protoliterate period (ca. 3500 – ca.2 900 BC), have been found. The most important city was Uruk, the Biblical Erech, and modern Warka in Iraq. The limestone temple was the main building on the fifth archaeological level of Uruk (ca. 3500 BC). Although its superstructure has not been maintained, some limestone remains have been preserved in a stratum of compact soil, which show us that it was a building with alcoves of a monumental size (76 x 30 m). Some structures from the fourth level of Uruk were lined with mosaics made of polychrome clay cones that were embedded in the walls, forming geometric designs. Another decorative technique was whitewashing or whitening of walls. This has led to a building built in the area of Uruk dedicated to the Sumerian god Anu being known as the White Temple, which had a shallow, narrow and long sanctuary inside. The White Temple stood 12 meters from ground level on a high podium, foretelling the typical Mesopotamian religious construction, the ziggurat; a stepped tower whose function was to bring the priests or monarchs a little closer to the heavenly gods, or to serve as a platform for the deity to descend upon to communicate with worshippers.

Exquisite stone sculptures have been discovered in Uruk. The most beautiful is the head of a woman or goddess made from limestone (ca. 3500 – ca. 3000 BC, National Museum of Iraq, Baghdad), which presumably had decorative inlays on the eyebrows, large open eyes and a deep central streak of hair. A ritual alabaster urn is also kept in the Museum of Iraq (3500 – 3000 BC), which divided into records, or horizontal bands. The upper band depicts a procession in which the king offers a basket of fruits to the goddess of fertility Inanna, or her priestess; naked priests carry offerings in the central band and in the lower one is a row of animals on top of plant shapes. The late Uruk period saw cylindrical seals, probably closely linked with the first use of clay tablets. Their cylindrical shape will remain as a common type of Mesopotamian seal over the next 3000 years. These small engraved stones were used as forms of personal identification letters and documents, covering them in damp clay to get a lasting imprint or a symbolic scene in miniature. The earliest seals show decorative motifs: bulls, priests or kings bearing offerings, cattle rearing, marine or hunting motifs, architecture, serpent-headed lions and other grotesque figures. Animals, real or imaginary, were created with great vitality, even when they were interpreted in a stylized way. The seal engravers’ art was just as important an expression of Mesopotamian culture as the civilization’s monumental arts.

This style of art developed in the and lasted until Babylon was defeated in 539 BC.

Many things developed from the Neolithic age to the fall of Babylon, such as the cultures and civilizations of the Akkadians, Babylonians, Sumerians, Kassites, Assyrians and Hurrians. Thanks to the appearance of diverse cultures and development, diverse artisanal and artistic materials and techniques emerged. Stylistic development also gave rise to various styles, shapes, and themes used in other periods.

Mesopotamia was a land that lacked certain materials such as wood, stone, and metals, but was rich in clay, among other materials. This favored the manufacturing of bricks, made of adobe, a mixture of mud, straw, and glass.

Mesopotamia was a very troubled area politically, socially and artistically. Its history is parallel to Egypt, beginning around 3000 BC, and its rivers were fundamental to its development, as they were in Egypt.

The civilization was based on a theocratic political system, dependent on priests, which is why their art reflected the interests of the state and the religious cult. This did not limit its originality or artistic value.

Factors that Classify Mesopotamian Art

Three factors are considered to classify Mesopotamian art:

- War was a constant concern, which meant that a good amount of art was dedicated to the glorification of military victories.

- Religion had a very important role in state affairs, so paramount importance was given to religious buildings. Most sculptures were for spiritual purposes.

- The influence of the natural environment. Being a civilization that lacked some constructive materials, like stones or wood, they had to use brick and adobe in their buildings – a mixture made from clay soil -, which are less durable materials. This is why so few traces of this culture remain.

Ancient Mesopotamian Architecture

Architecture was difficult in this era because the geographic location provided few usable materials, meaning that there was very little stone but abundant clay there. For this reason, the Mesopotamians opted to use brick and adobe in their architectural foundations.

Although the use of lintels (using wooden beams), vaults, and arches, was more common in Egyptian art, these three elements can also be seen in Mesopotamian art, and feature prominently in their architecture. The most notable difference between Egyptian art and this style of art was the little significance they placed on funerary buildings, only developing and focusing on two types of buildings: temples and palaces.

Major Monuments in Mesopotamian Art

Temples

These consisted of a large walled courtyard that would have its most characteristic feature in the space of one of its smaller sides: the ziggurat, which is a square tower consisting of several stepped floors, at the top of which is a shrine. Its sides face towards the four cardinal directions and a ramp that surrounds the four sides leads up to the different levels. Alternatively, were two symmetrical stairways that climbed up the front or sides, built using the richest materials like marble, alabaster, lapis lazuli, gold and cedar wood.

Palaces

These did not have a specific shape, and were a series of prismatic buildings of different sizes joined by hallways, galleries and corridors with spacious courtyards in between and surrounded by walls. They consisted of simple quadrangular structures with a central courtyard which provided them with light and ventilation. The interior walls were decorated with frescos on lime plaster, or with brightly colored enameled brick linings and reliefs. Some of the most important palaces were those of Nineveh, Khorsabad and Nimrud.

Walls

These were built to guard the cities, with vertical walls and cut at right angles, reinforced at intervals by square towers. Passage was made through fortified doors. These doors’ passageways were half-barrel vaults, and the customary protective statues were placed on both sides.

Tombs

Architecturally speaking their tombs are not of great interest, as they were simple hypogea with brick vaults and several chambers, which were marked from the outside by a small monument without any artistic value. Very rich funerary objects have been found inside: corpses of ladies, musicians, servants, coachmen and guards sacrificed in large numbers that reveal these peoples’ barbarous funeral customs.

Ceramics in Mesopotamian Art

Since the beginning of the Neolithic period, pottery has been the main distinguishing factor between material cultures and through it, it has been possible to observe diverse typological transformations, which were sometimes very delicate and ingenious. Using this, the pieces’ origins and archaeological contexts have been identified.

Normally, these types of figures were simply used as containers to transport and preserve various kinds of food and beverages. They were very useful as they developed a productive economy that traded over great distances.

Mesopotamian Metallurgy

In the middle of the 3rd century BC, metallurgy developed and flourished. Centuries earlier, objects that needed metal were made using metallic elements found in nature. However, with the flourishing of metallurgy in the 3rd century BC, other methods of acquiring metallic and mineral materials emerged. Precious metals also appeared with these new techniques, such as silver, gold, lead and above all copper, which stood out as the main material used, and shortly after it was mixed with tin or arsenic to manufacture bronze, which stood out for its resistance.

Mesopotamian Sculpture

In the absence of a hard foundation like stone, Lower Mesopotamia turned sculpture into a high quality and luxury product that was normally traded over great distances, and with this came the purchase of several products like Indian gems, African ivory, and Nordic amber. As Mesopotamian sculptures were luxurious and of a high quality, only some Mesopotamian kings could commission orders of statues. However, it is certain that cylindrical seals were widely used as identity seals on which they carved their own reliefs.

Although Mesopotamian sculpture was somewhat scarce, it had some main features such as the robustness and strength of its figures. The most commonly represented figures were humans, sometimes representing monarchs, gods, officials, etc., but always individuals, aiming to be a substitute for a person rather than a representation of them. For this reason, the head and face appear disproportionate in relation to the rest of the figure.

Human representations portray a total indifference to reality, without any likeness, while animal representations have a greater realism and fidelity to them.

Painting in Mesopotamian Art

Differences between paintings and reliefs can be distinguished:

Characteristics of paintings

They were strictly decorative, used to embellish architecture. They lacked perspective, and were poor in terms of colors, using only white, blue, and red. Tempera was used as a technique, and can be seen in decorative mosaics or tiles. The themes were war scenes of and very realistic ritual sacrifices. They depicted geometric figures, people, animals and monsters. It was used in domestic decoration, and a prominent feature was shadows not being represented.

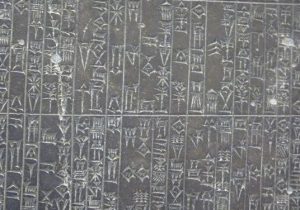

Characteristics of reliefs

They were common in platelets or narrative stelae, and some of these stelae feature cuneiform texts. They were detailed and meticulous works, which reflected a remarkable naturalism. In these works, a distinction can be seen between divine and human affairs. The king is depicted in scenes of war, banquets or hunting, always appearing as an upright figure, as they wanted to emphasize his power.

Although the most commonly used techniques in this style of painting were mosaics and marquetry, many of these great works can be found in the tombs of Ur. In addition, glazed bricks were used for decorative purposes in many structures, and were even used to make the reliefs of many figures.

Mesopotamian Art Timeline

The Early Dynastic Period

The earliest historical age of Sumerian rule spanned from around 3000 BC to 2340 BC. While old constructive traditions continued, a new architectural typology was introduced: the oval temple, an enclosure with a central platform that supported a shrine. The city-states led by rulers or monarchs who were not considered divine beings were located in Ur, Umma, Lagash (present day Al-Hiba), Kish and Eshnunna (present day Tell Asmar). Many of the objects made during this period are commemorative: reliefs depicting scenes of banquets, celebrations of military victories or the construction of temples. Many of them, such as the limestone stele (kept in the Louvre Museum in Paris) of King Eannatum of Lagash, were frequently used as boundary markers. This stela depicts the king at the head of his army in battle on one side, and on the other side the god Ningirsu, symbolically, and larger than the humans, holding a net containing the defeated enemies. The Standard of Ur (ca. 2700 BC, British Museum in London) is a board adorned with seashells, schist, lapis lazuli and pinkish stones showing religious scenes or processions arranged into three bands.

In the carved cylindrical seals, like in metal sculptures, mythological themes are the most commonly depicted motifs. In a large copper relief of the Ubaid temple (ca. 2340 BC, British Museum), an eagle with a lion’s head or a leptocephalus, with its wings spread, looms over two deer. Half man half bull figures were prominent motifs, as well as heroines fighting lions. However, these mythological motifs cannot be identified today. Finely worked objects such as crowns, daggers, urns and other decorative pieces have also been found. Between 1926 and 1931, Leonard Wooley found many of these in the Royal Cemetery of Ur (ca. 2600 BC). Two of the most beautiful objects depict two rampant (standing) goats (Philadelphia University Museum and the British Museum in London) resting their forepaws on a golden tree with symbolic rosettes at the end of its branches. The tree, the heads and legs of the goats are covered with embossed gold, their bellies are made of embossed silver, their skin with seashells and their beards, fur and horns are carved from lapis lazuli.

Sumerian sculpture, generally made from alabaster, exhibits a great variety in styles, and its geometric forms can be very expressive. They include figures making offerings, priests and rulers, some of them female. In the temple of Abu in Tell Asmar twelve of these have been found. These stone sculptures (2740 BC – 2600 BC, Museum of Iraq, Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, Metropolitan Museum in New York), with their arms in front of their chests and their hands together, have large, round, exaggerated, staring eyes made from seashells and black limestone. Slightly more naturalistic, the Louvre Museum has an alabaster seated male figure (ca. 2400 BC) from Mari. The architecture of this period in Mari (present day Tell Hariri, Syria), shows influences from western Mesopotamia.

The Akkadian Period

The Semitic Akkadian peoples gradually gained control of the area towards the end of the 24th century BC. Under Sargon the Great, who reigned approximately between 2335 BC and 2279 BC, they extended their rule over Sumer, unifying all of Mesopotamia. Although there are few traces of their art, the preserved remains show a technical mastery and a strong energy. In the Akkadian cities of Sippar, Assur, Eshnuna, Tell Brak and in their still undiscovered capital of Akkad, the palace replaced the temple as the most important building. A magnificent copper head from Nineveh (Museum of Iraq), which likely depicts Naramsin, the grandson of Sargon who reigned from 2255 BC to 2218 BC, emphasizes the nobility of these Akkadian rulers, who assumed the appearance of demigods.

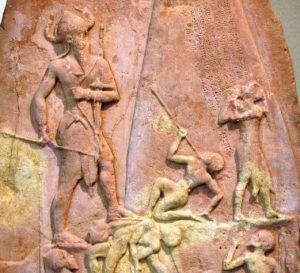

Naramsin himself is the protagonist of a skillfully made sandstone stele (Louvre Museum), which shows one of his victories in the mountains. The king wears a horned diadem, a symbol of divinity and, unlike in the iconography of the stele of Eannatum, the protector god is not recognized for his help in the military success. Heavenly forces are simply insinuated by the stars at the top. Perfectly adapted to the shape of the stone, the rhythmic movement of Naramsin’s triumphant army rising up the mountain and causing the enemy’s downfall stands out.

Seal engravers made use of the most significant Akkadian innovations. The small space on each seal was filled with lively scenes: gods and heroes fighting hand to hand against wild animals, monsters, and processional carriages. Scenes of offerings, in which an intermediary or a personified deity presents to another figure before a more important seated god, formed a thematic Akkadian innovation that evolved in the following eras. Some of the themes described in the Akkadian seals have been identified with stories from the Epic of Gilgamesh, although many of them have still not been interpreted.

The Neo-Sumerian Period

After ruling for a century and a half, the Akkadian Empire fell under the rule of the Gutians, nomadic peoples who did not centralize their power. This allowed for the Sumerian cities of Uruk, Ur and Lagash to reorganize themselves, thus beginning the Neo-Sumerian age, or the Third Dynasty of Ur (ca. 2121 – 2004 BC). In Ur, Eridu, Nippur and Uruk impressive shrines with ziggurats made with bricks and adobe were built. Gudea (ca. 2144 – 2124 BC), the ruler of Lagash, a contemporary of Ur-Nammu – the founder of the Third Dynasty of Ur – is known because of over 20 statues depicting him, made from two types of black and hard stones, dolomite and diorite. His hands are crossed in the old Sumerian style, but his round face and light musculature in his arms and shoulders show the sculptor’s desire to express more natural forms. The exception lies in the anthropomorphic figures that combine zoomorphic features, as they are more static than the rest of the sculptural representations. The most realistic representations are small reliefs and terracotta statues representing the faithful making animal sacrifices, legendary heroes, musicians and even a woman breastfeeding her son.

The Paleo-Babylonian Period

Following the decline of Sumerian civilization, Mesopotamia was once again unified by Semitic rulers (ca. 2000-1600 BC) like Hammurabi of Babylon. The embossed representation of the ruler in his famous legal code (ca. BC, Louvre Museum) is not dissimilar to the statues of Gudea, although his hands are not crossed, nor does he appear with an intermediary before the sun god Shamash. The most original art of the Babylonian period comes from Mari, including architecture, sculpture, metalwork and mural paintings. The representation of animals, as in most of Mesopotamian art, is more natural than that of humans. The small friezes from Mari and other cities show scenes of daily life with musicians, boxers, carpenters and peasants. These representations are much more realistic than those in solemn religious or official art.

The Kassite and Elamite dynasties

The Kassites, a people of non-Mesopotamian origin, appeared in Babylon shortly after the death of Hammurabi in 1750 BC, replacing the previous rulers around 1600 BC. The Kassites adopted Mesopotamian art and culture. The Elamites from the west of Iran destroyed the Kassite kingdom around 1150 BC. Their art seems to be a provincial imitation of the first Mesopotamian styles. In fact, their admiration of Akkadian and Babylonian art led them to take the stele of Naramsin and the Code of Hammurabi to Susa, their Iranian capital.