Food in the Ancient World: Humanity’s Most Important Achievement

Contents

In order to understand the evolution of food in the Ancient World and certain norms that would be labelled as hygiene habits today, as with studying the Middle Ages, we need to differentiate Early Antiquity from Late Antiquity.

The former began with the appearance of writing in around 3,300 BC, in the case of Ancient Egypt and some Mesopotamian peoples, and lasted until the 5th century BC. Late Antiquity spanned from this time until the 8th century AD.

There aren’t any specific documents from the first period, nor from much of the second, that talk about food, much less so hygiene. Everything we know has come from archaeology, either through graphic or monumental expressions or simply through analysis of waste in domestic containers. Thus, we know much more than imagined at first sight.

There’s a lot of documentation from the second period (the period closest to us), and the closer you get, the more there is. However, usually, it has to be taken from generalized texts.

Historians divide ancient civilizations into two categories: mainly agricultural cat ones (Egypt), and livestock based dog ones (Assyria). However, for anthropologists, these two animals represent carbohydrate and protein based civilizations.

Through carbon analysis of mummies or just bones that have been unearthed, these two cultures show a difference in height and longevity favoring livestock farmers. We also know that while there are still purely agricultural civilizations around today, civilizations that have livestock combine it with agriculture; where cattle fodder grows, so does cereal. At present, there is a tribe in Africa, the purely protein-consuming Tutsi, who feed on blood, bone marrow, and meat.

Slow Changes

As analyzing the Ancient World’s entire range of food in one post would be beyond impossible, as well as ambitious, it’s appropriate to begin by looking into an intermediary point in time in Egypt: the Nineteenth Dynasty of the New Kingdom, from around 1310 to 950 BC, or the Ramesses’ Egypt. To make up for the centuries omitted, it’s enough to know that unlike other ancient civilizations, social aspects were very slow to change in Egypt.

Interest in the Nineteenth Dynasty, in addition to corresponding to a period of great splendor in all facets, is especially well documented. In the arts, great temples were constructed during these years, among them two very important ones: Karnak and Abu Simbel.

It also coincided with the life of Moses. The Old Testament says that Moses, brought up by the Pharaoh’s sister, was educated and lived in court until he was 40 years old. Due to a series of problems he was forced to flee, and at 80 was chosen by Yahweh to free the Jewish people captive in Egypt.

It also coincided with the life of Moses. The Old Testament says that Moses, brought up by the Pharaoh’s sister, was educated and lived in court until he was 40 years old. Due to a series of problems he was forced to flee, and at 80 was chosen by Yahweh to free the Jewish people captive in Egypt.

During his journey through the desert, God, in addition to giving him the Decalogue, gave him a set of rules for everyday life. These rules covered legislation as well as food and hygiene, and in many cases were identical or very similar to those of the Egyptians. This set of rules known as the Law of Moses would remain, apart from modifications of rituals, in religions as important and relevant to us as Judaism, Christianity and Islam.

We see an abundance of agricultural products in different papyri during the first pharaonic dynasties, with some birds, a few ruminants, hunting being a sign of distinction, and the odd fish. As time progresses, we see the spectrum of food increase considerably.

Bread: A Staple

The staple food was bread, but there was a notable difference between those made from wheat flour for the wealthy class, and those from rye flour for the less well-off. We’re aware of more than 16 kinds of breads, among them sweet and savory ones.

During this time, the consumption of meat took on a major role. The constant presence of a species of African ox, called an iwa, in the pharaohs’ feasts is seen in the papyri, primed and ready for the banquet. There were also lamb and goats, and gazelles and antelopes from the hunt.

However, the cows were small, skinny and used in agriculture. As a result, milk production, although highly appreciated, was scarce. This shortage was mitigated with sheep and goat’s milk, especially when manufacturing cheese and butter.

Unlike the rest of the peoples of the Mediterranean Basin, the consumption of pork was unusual. With the arrival of the Ptolemaic Dynasty (4th century BC), it was found on the tables of the foreign population. This lack of interest in the consumption of pork among the Egyptians turned into a total prohibition under Mosaic Law, and was a serious sin. As a result, practitioners of Judaism and Islam do not eat pork to this day.

Here we should pause for a moment and explain the process of sacrificing cattle for human consumption. Cattle were sacrificed in temples, either by a priest or by an authorized slaughterer and no one could consume meat from any other source. The high local temperatures forced them to consume the whole animal within four days at most. All relatives came to share the meat at the slaughter.

The priest or the slaughterer pierced a precise hole in the animal’s jugular vein, through which the blood was drained. They then disinfected and removed the skin. Before cutting its throat, its entire body was washed softly with a white linen cloth dipped in a solution of water with a little natron (sodium carbonate). Like blood, the viscera and bone marrow were avoided to prevent possible disease, and the meat was eaten cooked or roasted. Even today, practitioners of Mosaic Law (Jews and Muslims) do not eat beef if it has not been sacrificed by an official and under certain rules, traditions that share a certain similarity with the process described above.

As for vegetables, they liked onions, cucumbers, garlic, leeks, radishes, carrots, turnips, spinach, and naturally they couldn’t do without their cherished lettuce, which ensured that men would fall in love and women would be fertile. Most of these vegetables were eaten raw, since the Greek Diodorus (1st century BC) wrote in a rather perplexed way about lettuces, and was used to eating them raw rather than cooked.

Their legumes were like ours today: peas, lentils, beans, and chickpeas. For fruit they had dates, grapes, pomegranates, apples, coconuts, figs, watermelons, melons, and blackberries. With Roman occupation from the 1st century BC, pears, peaches, almonds, and cherries were introduced. These legumes, fruits, and vegetables would be common throughout the whole Mediterranean Basin in abundance. Throughout the Ancient World, garlic wasn’t just a delicacy but also used to treat rheumatic pains.

Legumes were cooked and some, such as chickpeas, were roasted after being sprinkled with lime (Berlin Papyrus). They, especially beans, were also dried in the sun to be preserved for consumption outside of season.

Prepared Cuisine

It’s not until the Ancient Greeks, and especially the Romans, that we can discuss prepared cuisine. The concept of stew, or the mixture of various ingredients to create different tastes, has its origin in less affluent classes, and in their eagerness to make the most of everything others discarded.

Salt came mainly from mines, it was only in the Nile Delta that was produced in salt lakes, and although it was rarely used in flavoring food, it was needed for preserving fish. Social position also had a hand in sweetness: the wealthy classes obtained it from honey, while the rest of the people got it from ground carob tree seeds.

The drink par excellence was beer, which due to a lack of hops was flavored with herbs (rosemary). Although in this period, wine, which had appeared a few decades earlier, was considered essential in the feasts of the wealthy; its consumption and abuse was notorious.

Although fishing was practiced as a sport and as a profession, fish was for the tables of the less well-off. It was preserved for long times, either dried in the sun or salted,

With the arrival of the Ptolemaic Dynasty (4th century BC), and given that the new Pharaohs consumed it, fish enjoyed a better reputation. We know this as it;s documented that when Cleopatra went to meet Mark Anthony, she offered him a menu on her boat consisting mainly of oysters, cooked octopus, and lobsters.

In Greece, and more so in Rome, the cook’s profession became very important, and their recipes became real books. We know that Julius Caesar traveled with his cook who constantly prepared different dishes, and there is documentation attesting to this.

Although hens and chickens were around, they weren’t wanted on the tables of the Egyptians. Again, their consumption would become popular with the Romans. Empress Faustina, wife of Marcus Aurelius (161 AD), mitigated the discomforts of childbirth by having chicken soup during her postpartum quarantine. One of life’s ironies, or in recognition of the chicken soup, her son and future emperor would be called Commodus, the Latin root for the word ‘comfortable’.

The Egyptians, in addition to their religious festivals, had a series of lucky and unlucky days in their calendar. During the unlucky days, in addition to the prohibition of certain activities, fasting was practiced. Again, this fasting can be found in Christian Lent, in Islam, and in Judaism.

They were also bound to following standardized hygiene rules. They had to wash several times a day: before they rose, and before and after each meal. They had three meals, and the most important was at noon when they sat down to eat.

Natron as Soap

Natron was used as soap for daily cleaning. They painted their eyes into fish shapes with malachite powder to get green, Galena for black, and antimony for azure. This tradition wasn’t just a way of flirting, but a way of avoiding ophthalmological diseases, especially trachoma.

Circumcision was unusual and less necessary for Egyptians, but we know that it was practiced in disadvantaged circles. Types of curved blade knives and some depiction of it in papyri have been found.

Circumcision was unusual and less necessary for Egyptians, but we know that it was practiced in disadvantaged circles. Types of curved blade knives and some depiction of it in papyri have been found.

Doctors’ roles were performed by priests, and the closest thing to our hospitals were “The Houses of Life”. Trepanning operations in ears are well known, but the treatment of diseases of psychosomatic origin really stand out in the numerous documents we possess.

Healing techniques for these patients consisted of a combination of music and smells. Incense was essential in palaces, temples, or crowded places for its antiseptic and sedative properties, or simply to mask bad odors. Due to its high cost, terebinth ash was burnt in poorer circles.

Body perfumes for men and women were used daily. They were obtained by distilling plants along with a fatty element, oil or butter for the poor, and turpentine (cedar resin) for the more affluent.

Personal grooming was very important. To remedy sagging skin, they put on masks composed of alabaster powders, natron (sodium carbonate) mixed with honey, or beaten egg, or just honey. Bad body odors were covered up by rubbing the body with mint, but if they persisted an ointment was prepared from terebinth and incense. For more passionate times, they perfumed themselves with myrrh.

Among the aromas considered special were those extracted from mummies, which were practically soaked in aromatic oils. During the Ptolemaic Dynasty, 2nd century BC, many mummies were sold to the kingdoms of Asia Minor in times of economic hardship. However, the real trafficking of mummies to extract their oil lasted from the Early Middle Ages to barely 100 years ago.

In the 19th century, a type of panacea pill was manufactured in pharmacies using mummy oil (Judea bitumen) collected in a paraffin or wax capsule. It was said to alleviate all kinds of pain, and even heal people. So great was the demand that they ended up selling new mummies, made for the occasion, to be sold as authentic old ones.

Speaking of Mummies

Continuing with mummies, and out of curiosity, we have to remember that Napoleon Bonaparte, on his return to France from his Egyptian expedition, took with him, among many other things, the mummy of the famous Cleopatra installed in the National Library. However, during the Siege of Paris in 1871 they made the mistake of transferring it to the basement to protect it, where it rotted due to the humidity. In the Library’s diary, it’s noted that “in light of this, it was given a worthy burial,” but by omitting the location the remains have disappeared.

Men and women shaved their whole bodies, including their heads, thus avoiding unwanted parasites. They had different wigs as we see in the papyri. Only upper-class males wore rectangular beards.

Dress should be mentioned out of curiosity. There were some clothes for men that covered the chest to the ankles and were strapped, but most preferred pleated linen skirts that allowed the neck to breathe, and a large belt shaped around the waist. All this was adorned with a display of jewels, necklaces, breastplates, and bracelets. Ladies, in their nakedness, wore a kind of transparent shirt tied to a shoulder leaving a breast exposed, and a quantity of jewels similar to the men.

The servants of the house went around naked, especially when their masters received guests. Sandals were the typical footwear. Sandals with soles and bands made of gold can be found in museums, which, in addition to being uncomfortable, must have caused injuries when worn. Medical papyri in Leiden tell us how the Egyptians often hurt their feet.

Inhaling crushed willow root was typical when treating neuralgia and rheumatism. In fact, all parts of the willow were used for different purposes. Centuries later, the Bayer pharmaceutical company put a pill composed of acetylsalicylic acid on the market, and would name it Aspirin. The Hebrews, Persians, and Assyrians discovered that there was much more acetylsalicylic acid in spikenard bulbs than in willows, and increased their cultivation. This flower was worshipped so much that it is the Jewish national flower even today.

Domestic Hygiene

As for health at home, all possible human and divine methods were used to get true domestic hygiene from the earliest dynasties. The exterior of the dwellings depended on the economic position of the owner, but the interior always had to be whitened or else they’d be evicted.

To prevent flies from gathering, oriole grease was used in a container, as is done in various countries in North Africa and the Middle East; they crushed their eggs before they were incubated, and it also served as an ointment to protect against flea bites. A cloth covered with cat grease drove rats and mice away from the area. To protect granaries from unpleasant visitors, their floors and walls were covered with animal urine and excrement solutions (uric acid).

Inbreeding in marriage wasn’t just common, but a religious doctrine especially among the pharaohs and the upper class. We do not have any documentation on the physiological defects as a result of these unions.

Inbreeding in marriage wasn’t just common, but a religious doctrine especially among the pharaohs and the upper class. We do not have any documentation on the physiological defects as a result of these unions.

The richest peoples of Asia Minor, what we know today as the Middle East, were undoubtedly located in the Tigris and the Euphrates River Valley. It’s with good reason that it’s been said that Eden was here, as well as the poorest Hebrews. The first would be the Persians, advancing already at the time, with their most characteristic city, Babylon (modern day Iraq), where abundance, luxury and excess manifested themselves in all ways of life. The second would be Israel, which, with the exception of a valley in Galilee, had very limited resources.

A contemporary of theirs was ancient Greece. Their agricultural and livestock resources weren’t just poor, but also scarce. Instead, they had a large sea that mitigated their hunger, and they knew how to make up for their inexperience with intelligence and determination.

In the 5th / 6th centuries BC, customs, food and hygiene rules were fully established in Athens.

Their vegetables and legumes were the same as those described in Egypt, but more scarce. So much so, that although they were common in peasant’s diets, they were considered elegant in the cities due to their high cost. There was only one original Greek vegetable: the artichoke, which was eaten raw. Years later, under Roman occupation, it was despised for blackening teeth, but it reappeared as cooked under Emperor Augustus.

Cereals were the same throughout the Mediterranean Basin with the exception of wheat, for the most part, which was imported from Egypt and Syria. Its high price made wheat flour bread somewhat unattainable, with oats being the most consumed cereal.

Rice entered the Greek diet after Alexander the Great’s expeditions to the East (325 BC), and Theophrastus (372-288 BC) in his work Historia Plantarum, was the first to describe its cultivation and how it was cooked.

However, there was a difference between the Egyptian and the Greek population’s tastes in regards to flavoring food. While the former liked to add grease or butter to their food, the Greeks used olive oil.

One of the most highly-valued vegetables was cabbage, and Pythagoras recommended it for its positive attributes. Several of his writings have lasted to the present day. It’s said that to become an octogenarian, Diogenes stayed in his famous barrel consuming only cabbage and water.

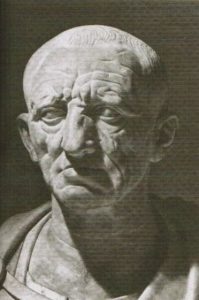

Cato’s Recipe

The censor Cato recommended it in a vinaigrette and cooked as medicine. The historian Pliny (1st century) wrote that a “giant version” of the cabbage had been obtained, which, to the poor’s good fortune, “caused the table to overflow.” In the 1st century BC the Greeks and Romans fermented cabbage due to its low cost and to preserve it for longer, and found it useful as food for the troops. It’s believed that during Emperor Marcus Aurelius’s campaigns in Germania he passed through present day Germany, giving rise to the well-known dish sauerkraut.

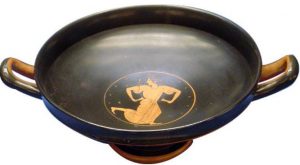

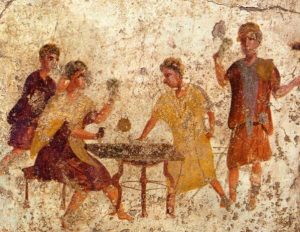

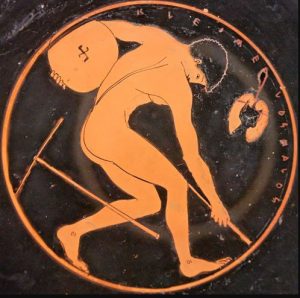

The Greeks were generally quite austere and modest with food, but this did not diminish their taste for banquets and their resulting excesses. Perhaps it is because these were exceptional events that they were represented so frequently in their ornamentations.

The Greek words symposia and symposium, used today to describe serious and important meetings, are somewhat different from their classical meanings: a banquet and the part of the feast where they exclusively drank, which translates to “a gathering of drunks” in Vulgar Latin.

The most important meal of the day was dinner. It was eaten lying on a couch, with one’s back straight and made comfortable with several cushions. Unlike Egyptian traditions, women were excluded from these symposia or banquets. The guests had to be distinguished into two classes: the diners themselves and those who only had access to the symposium, meaning the drinkers’ gathering.

With the impoverishment of the old families in the wake of the nouveau riche, who owed their fortune to trade, the figure of the parasite appeared. Normally they were good people, who’d fallen on hard times, and were invited to banquets for the host to show off due to their eloquence and culture.

For drinks they had mead, a blend of water and honey, and a brew made from barley and water, flavored with different fragrant herbs such as pennyroyal and thyme. But wine had the real leading role. It was drunk without fermenting it, or artificially fermenting it with salt water, but one way or another, they always added water when it was consumed, and in some cases honey, thyme or cinnamon.

Doctors attached great importance to body care and physical exercise. Gymnastics was considered essential for health, for both men and women. Socrates himself, in his old age, practiced it to reduce the size of his belly which, according to him, had exceeded its appropriate size.

There are three characteristic traits in Greek gymnastics: nudity (gymnastics derives from gymnos which means “naked”), applying body oil, and the sound of the oboe. From an early age, children learned to bathe and swim on riverbanks or by the sea, and by the age of eight they began to practice gymnastics. Lower class women made the most of fetching water from fountains by bathing under their spouts.

These were high-up in order to provide showers. However, it was strictly forbidden to bathe in the pond where they got their water from to avoid any contamination.

Athletes and men who used public toilets could not go into shared swimming pools without having showered.

The Greeks used to walk inside their houses barefoot, and the poor also did so in the streets. In order to provide relief from walking, it was customary to find channels on public roads to cool one’s feet, and in household courtyards they were an essential.

They bathed before dinner, so the verb bathing used to be synonymous with “I’m going to have dinner”. Since they did not have soap as we understand it, they used a crude carbonate of soda, extracted from the ground, or even a potash solution made from wood ash, just like what was used to wash clothes. Men didn’t shave until Alexander the Great, but women did shave using a razor blade.

A depilatory cream made with donkey sperm came with the Roman occupation but due to its high cost, it was only available to wealthy ladies. Hair was also bleached with potash to get a blond color, or with temporary dyes to get red, blue, or green hues.

Arriving in Rome

With everything above explained, we reach Rome and above all Imperial Rome, which is impossible to describe in just a few lines.

If we look at the time of the emperors Hadrian and Trajan as an outline, halfway through the 2nd century AD, it has nothing in common with the social situation in the previously described worlds. As for food, all products known today, except for those of American origin, were available.

Appreciation of the taste of food developed and an indispensable figure emerged in wealthy Roman families: the expert cook. We even have cookbooks from some of them, as well as the high fees that they charged.

Roman society in the first centuries of the Empire was cultured, curious, thirsty for novelties and snobbish, but never vulgar. Over the centuries they became prone to excess and with it disorder.

All these achievements of the Ancient World, both in food and hygiene were lost for centuries with the Dark Ages. Not only did they disappear as customs and as ways of life, but the cultivation of certain plant species was also forgotten. With forgetfulness comes famine, great pestilence, and misery.

In the Modern Age, from the Renaissance (14th century) to the present day, we’ve achieved, not without effort, great advances in all fields. However, we run the risk of this apparent “opulent” culture in which we are absorbed sapping us of the enjoyment of basic foods and making us forget the importance of good nutrition. Hopefully not, as taste is still one of our five senses and we should not be willing to lose what is ours and has been cultivated for centuries.