How was the ancient civilization of Persia? In this article, we will discuss the development, economy, government, and society of the Ancient Persian Empire.

Ancient Civilization of Persia

Contents

- Ancient Civilization of Persia

- Location of the Ancient Persian Civilization

- The Persians

- Organization of the Persian Empire: Unity in diversity

- Economy: the support of the colossus

- The Persian Society

- Religious aspect: “Thus spoke Zarathustra”

- Agriculture and Livestock

- Persian Art: An art for the monarchy

- Legacy of the Ancient Persian Civilization

Location of the Ancient Persian Civilization

The Persian civilization developed in what is current Iran. It is a plateau in Asia, neighbor to Mesopotamia, which was a witness to important historical events. This plateau, which occupies two million square kilometers, can be delimited:

- To the West: the valleys of the Tigris and Euphrates (from which they are separated by the Zagros Mountains);

- To the East: the Indus River Valley;

- To the North: the Caspian Sea and Turkestan;

- To the South: the Persian Gulf and the Indian Ocean.

The heart of its territory is a desert zone, surrounded by high mountains. The fertile lands, fit for cultivation and livestock, are found on the slopes and the valleys of these mountains. In the present, the region is occupied by the states of Iran, Afghanistan, and Pakistan.

In ancient times, it was the site chosen by two peoples to settle and develop their civilization: the Medes and the Persians.

These peoples belonged to the linguistic family of the Indoeuropeans or Aryans also integrated by the Hittites, the Mitanni, the Kassites, the Ionians, the Eolians and the Achaeans among others. On comparing the characteristics of their languages, it was supposed that they formed a people which at one point was united. Their place of origin can not be precisely established: it could have been in the North of Europe (in the region of present-day Poland), the center of Asia or the zones near the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea. The first element which made them powerful was the domestication of the horse, which constituted a new and important military resource. Later on, the utilization of iron and war chariots would make them into fearsome warriors.

As they went on expanding, they settled in different areas and formed distinct nations. The Hittites, for example, settled in Anatolia; the Ionians, Eolians and the Achaeans, in Greece; the Indians, in the Indus and Ganges river valleys.

Towards the end of the second millennium B.C., the Medes and the Persians arrived in the fertile valleys of the Zagros Mountains.

In the area parallel to Assyria the Medes settled, and over the Persian Gulf, the Persians installed themselves.

The Medes

A people of Aryan shepherds, on settling they began to practice agriculture. Their organization was initially tribal, that is to say, they were divided into tribes which would unite, in the case of war, against a common enemy.

In the 9th and 8th Centuries B.C. they were subdued to tribute by their powerful neighbors in Mesopotamia: the Assyrians, who also dominated the Persians.

At the end of the 8th Century B.C., the Medes organized a state and subdued the Persians. They remained under Assyrian dominion just the sam until their king Cyaxares united with the Babylonian king Nabopolassar and together they planned to put and end to the Assyrian domination. This undertaking was successful.

At its end, Cyaxares and the Chaldean king divided the territories of the Assyrians; for the Medes was left Upper Mesopotamia and western Iran.

Its hegemony ended in the 6th Century B.C. when a new power arose, that of their brothers the Persians.

The Persians

The ancient Persians would develop a new expansion policy which would turn them into the owners of the Near East.

In the beginning, they were divided into 10 or 12 tribes, whose chiefs had the title of King. There was no agreement between them to unify in one tribe, because of which they suffered the domination of the Medes. According to tradition, Achaemenes, who guided the Persians toward the South, founded the Achaemenid dynasty, to which the great kings who would come later belonged.

But it was Cyrus who achieved the unification of the distinct tribes into which the Persians were divided, to later overthrow the Medes and put and end to their supremacy. Cyrus converted the city of Susa into the capital of the new state in 550 B.C. and decided to begin a policy of conquests of the neighboring territories.

After imposing himself over the Medes, he directed himself against the Lydian kingdom. This kingdom, located on the coasts of Asia Minor, was famous for its richness and for being the vital center of communications, given that the routes of commerce with Greece passed through there.

Cyrus also incorporated the Greek cities of Asia Minor into his dominions. He directed himself next against the Neo-Babylonian Empire, which he conquered quickly; he annexed thus Mesopotamia and its Syrian dependencies to the Persian dominions (1538 B.C.). On his death, his son Cambyses continued the expansive work, directing himself towards Egypt and conquering it easily (525 B.C.)

During his absence, the Magi Gaumata, representative of the sacerdotal clan, provoked a revolt and took the throne. Cambyses tried to return from Egypt but died suddenly on the journey. Darius, the husband of a daughter of Cyrus, organized a rebellion of nobles against the usurper of the throne, the Magi Gaumata, and overthrew him. Thus he became the new king of the Persians. He would be the true organizer of the empire, and with whom it would reach its greatest splendor.

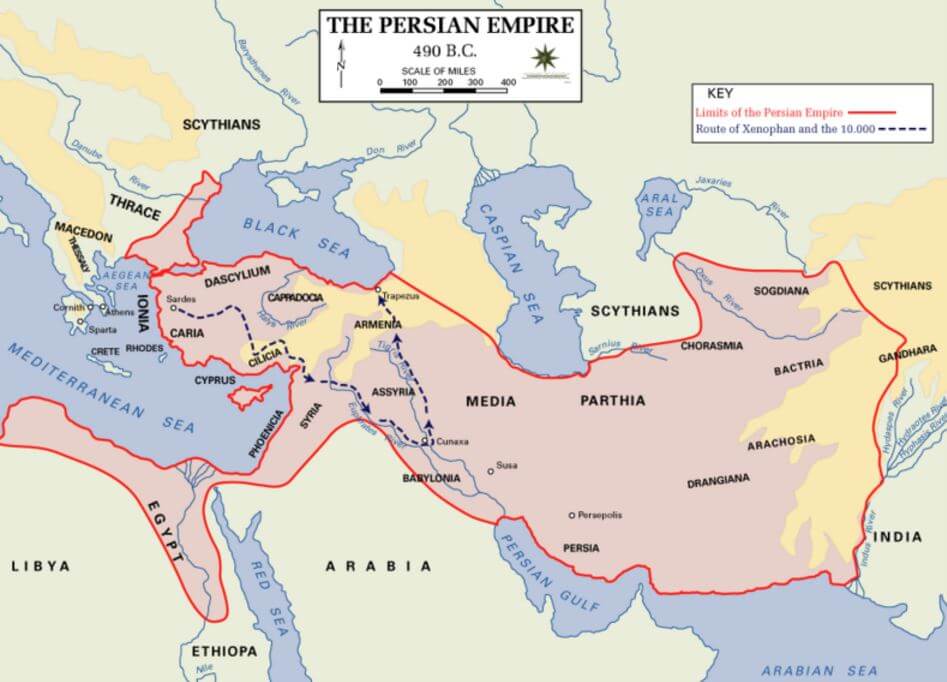

The Borders of the Persian Empire

The borders then reached their maximum extension. Darius conquered to the East all the territories as far as the Indus River valley, and to the West, Thrace and Macedonia. Later, he tried to subdue the Greek cities, which provoked the First Greco-Persian War. This campaign, in 490 B.C., was Darius’s only failure. Ten years later, in 480 B.C., his son Xerxes again attempted the conquest of Greece, giving rise to the Second Greco-Persian War, but he failed just like his father.

The Persian Empire was sustained, in one way or another, for 150 more years, until in 330 B.C., it was incorporated by Alexander of Macedonia into his empire.

The primary objective of Persian politics was to achieve a universal hegemony: that is to say, the conquest of all the known territories of the time.

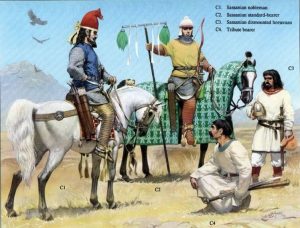

The superiority of their army was owing to the tactic of assault with archers on horseback. It was made up of 10,000 warriors called “The Immortals” because their number did not change in spite of losses, given that these were immediately replaced to keep the number constant.

Synthesis of Persian conquests

- Cyrus: Media, Asia Minor (Lydia), Babylonia, Syria, and Palestine. Iran to India.

- Cambyses: Egypt and expeditions to the surrounding areas (Ethiopia, Libya)

- Darius: Territory to the Indus River Valley, Thrace, and Macedonia (to the west)

Organization of the Persian Empire: Unity in diversity

The great empire of the Persians had a well-organized structure different from other empires, like the Assyrians, who based their dominion only on terror.

Organization was a pressing necessity for the Achaemenid Empire. They managed with great ability the mosaic of countries of diverse races, religions, languages, traditions and economies which formed their State. They generally respected the leading class of each region, to which they added a Persian administrative apparatus controlled from the great capitals like Pasargadae, Persepolis, and Susa.

In addition, they tolerated the traditions and cultural manifestations of the subdued peoples. Their principal concern was the regular payment of tribute. Thus they divided the empire into twenty provinces or satrapies. Each one had to deliver yearly a determined quantity of its characteristic products: metals, precious stones, grains or livestock.

To facilitate communications they constructed the great royal road, which crossed all of the Near East from Anatolia to Iran. In its trace posts and relays were placed, by reason of the extent of its reach.

The Persians were the only ones exempted from the payment of tributes. They held the charges higher up in the hierarchy, as much on the administrative level as on the military.

At the top of the empire, the monarch was found. The power of the king was absolute nothing nor no one was able to compete with his authority. The Persians had the idea that the king received his authority from their god (Ahura-Mazda) by whom he was chosen. The monarch, in addition, should be the model for all his warriors: riding on horseback, shooting a bow and be the leader in physical exercises. He was called the Great King or the King of Kings.

The imperial administration was made up of various officials:

Satraps were Persian nobles who were at the head of a province or satrapy. They represented the king in the province and considered themselves united to him by a knot of fidelity in defense and administration of goods. They occupied themselves with the collection of tributes, the maintenance of permanent armies and with mobilizing the population to cooperate in public works. They were considered the highest judicial authority in the territories in their charge.

Secretaries completed the functions of royal advisers of the satrap. The king named them directly. Among their responsibilities was found that of investigating the governor of the province.

Inspectors formed a body of auditors who controlled the interests of the king, watching the satraps. They were called the eyes and ears of the king because they informed him of all that happened in the empire and if his orders were carried out. If the circumstances called for it, they could dismiss the satrap.

In synthesis, the imperial policy followed by the Persians tried to reconcile unity with diversity, respecting, on the one hand, the regionalisms in culture and traditions, and imposing, on the other hand, a centralization in the payment of tributes and the provision of military services, decisive elements for their survival.

Economy: the support of the colossus

As we saw, the economic organization of the colossal Persian Empire was tributary. All the provinces were subject to the payment of taxes, whether in kind or in ingots of precious metals, in accordance with their productions. Egypt sent wheat; the region of Media, livestock (sheep, mules); the satrapy of the Indus, hunting dogs and auriferous sands. Other peoples, although not integrated into the empire, also sent gifts; for example, Ethiopia sent gold, ebony wood, and elephant tusks.

The political and administrative unity which they imposed facilitated exchanges. The merchants had greater security and better systems of communication for their work. This implicated a great development in commerce, which was favored in addition to a new custom: the utilization of money. Conceived as an issued metallic piece, it was useful for facilitating exchanges and as a common measure for the price of objects. Its invention is attributed to the Lydians, who formed a State on the coasts of Asia Minor, where an important commercial route passed.

The Persians, on incorporating the Lydian kingdom into their empire, took the monetary custom and imposed it throughout all their State. That is to say, they spread the use of money throughout all of the Near East. In this way they made a great contribution to commercial development; the difficulties which barter produced for the exchange of merchandise diminished and the transactions took on greater agility and speed.

The Persian Society

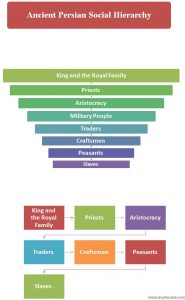

Society was divided into different hierarchies, in accordance with their privileges and occupations.

The highest class was made up of nobles. Within it, the priests and magi were very important. They directed worship and were political advisers of the kings or of the governors of provinces. They could also administer justice, based on the law of retaliation. Among the nobles, those who belonged to the Achaemenid family were more important. The king was obligated to choose a wife from among the women of this family. The inferior sector of society was made up of businessmen, artisans, and the peasants.

For decoration enameled bricks of various colors were utilized, which combined formed friezes. Lines of soldiers, figures of animals and scenes of payment of tributes were represented in relief. Regarding funerary architecture, they conceived graves and monuments more simple than those of the Egyptians. Some of them were created through the excavation of rocky slopes and mountains. In their interior, only a hall and a room without paintings nor sculptures were found.

Society and Daily Life

As in all of the nations of the era there always existed social inequalities: the society was very hierarchical, and the distinct social sectors were separated by very rigorous barriers. At the top of the pyramid was found, naturally, the king.

Immediately beneath the sovereign, we find the representatives of the great families of the Persian nobility. From the aristocracy of the Persians and Medes came the personnel of the court, and from its heart, the satraps were recruited. Some of the sovereigns of conquered countries were elevated, at times, to the rank of satrap without, however, being assimilated into the Iranian nobility. This aristocracy was occupied, above all, with war and hunting. The great mass of the population was made up of the peasants, who were free men, who could be landowners as we have already seen.

Between the nobility and the rural masses were found the priests or magi, who, in spite of the religious reforms realized by Zarathustra (also called Zoroaster), occupied a very important place in the empire. They never completely renounced their political ambitions, and the kings frequently tried to limit their influence.

In the secondary categories the artisans were included, sometimes confused with artists; the architects, engineers, etc. Apparently, there are found in the Persian society elements of a social organization of castes, which is normal in an Aryan people, related to those who established the system in India after conquering it.

The Persian were not hostile to foreigners and received them gladly, but did not integrate them into their society. Their hospitality was proverbial; they were, many times, the last refuge of the Greeks expelled from their country and persecuted by the longing for vengeance their compatriots had.

Of course, not all men lived in an identical manner according to their social rank. We are especially informed about the high classes of the society. It is know that the peasants were illiterate, as in the majority of ancient societies, and they were subject to the cycles of agricultural work.

Zoroastrianism exalted the rural life, and of working the ground said that it was the most pleasing to Ahura-Mazda. The peasants were called, periodically, to serve in the provincial contingents of the army.

In the other social classes children were instilled, from their most tender infancy, with the hate of lies, a sense of justice, honor, and respect for giving one’s word. Xenophon says that in school children learned justice like among us they learn their letters. In addition, the use of arms was taught to them, like the bow and spear; their bodies were toughened through numerous physical exercises, races, etc.

With this it was attempted to temper, at the same time, the body and the spirit. The food given to the young people was frugal, and would always continue to be so, as the Persians, used to eating little during their youth, maintained this habit throughout their life.

The foods consisted of some biscuits made of grains, meat, according to the luck of the hunt, and fruits. They only drank, habitually, water. The sumptuous feasts, whose record obsessed the ancient writers, were infrequent, and in them only a very small part of the population participated: the sovereign and his guests, some satraps, above all those of the western provinces, like Lydia; it was more about a pre-Achaemenid tradition than a custom introduced by the Persians.

Under the successors of Darius, and above all in the 4th Century, when the customs were relaxed and high classes lived in luxury and even licentiousness, the expression was born: Living the life of a satrap. The suit of the classic era was simple and nearly uniform. Only the richest classes added a note of variety, above all in the selection of cloth and greater luxury in ornamentation. In this also the times of Darius must be differentiated from those of decadence. The Greeks, on the other hand, spoke much of the fondness of the Persian for gold.

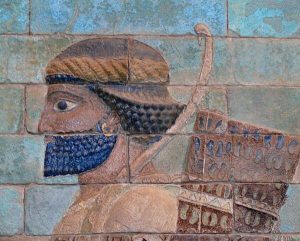

These, effectively, used the precious metal whenever they could, to adorn their suits and also those of their children. But it is necessary to see in this fondness not only a pleasure of an aesthetic nature, but also a religious fact: gold is the metal which evokes fire, the sacred element. It has been said also that the Persians were very modest and that they covered the greater part of their body. They wore a type of shirt of fairly fine cloth, over which they put on two tunics with long sleeves which, at times, covered their hands.

These tunics were of colors, different in summer and winter, and purple was the color preferred by the kings and the greats. They tightened these tunics at the waist with a leather belt. They wore, in addition, pants of cloth or sometimes leather. They were shod in sandals, which completely covered the foot and could go as high as the length of the leg. In winter they added to this a cloak. The women seem to have worn a suit very similar to that of the men, but certainty can not be had because there exist very few representations of feminine figures.

The richest adorned themselves with jewels, necklaces, bracelets and chest-pieces. The Persians, especially after Darius, and only in high society, employed abundant shaves, perfumes, and haircuts. These effeminate practices were shown to them by the Lydians. The daily behavior of the Persians was impregnated with moderation and urbanity, which contrasted violently with the conduct of the Greeks, who, nevertheless, called them “barbarians.”

They considered personal hygiene as a show of courtesy to their neighbors; relations between people were ruled by a rigorous etiquette. Greetings were always deep and respectful, as much between equals as between inferiors and superiors.

All excesses in behavior were condemned. According to Herodotus, Xenophon and Strabo, the Persians did not eat in the street; blowing one’s nose or spitting on the ground was proof of a poor education. The Persians were polygamous and had concubines, especially the great characters, as, for the rest, the maintenance of many women was too costly. The family was respected and tradition promoted the birthrate. Having a great number of children was considered a divine blessing.

Weddings were celebrated very early; frequently during puberty, and were arranged by the families. The woman was never in inferior conditions; she went about freely and could be a counselor greatly taken into account. It should be specified that in the last era, it was considered of good form among rich families to keep women closed in, which never happened with the other social classes.

They were innovators in religious matters, but their legacy was poor in the other fields of intellectual speculation. Only some fragments are conserved of their greatest written work, the holy book of Avesta. The Persians contented themselves, in this area, with keeping in check the peoples who were subdued by them; the same happened with the sciences and with medicine, which they copied from Babylon and Egypt. The sovereigns surrounded themselves with Greek doctors. They knew and sometimes appreciated Greek literature and philosophy. Apparently, they had an important oral literature, but no vestiges of it have been left. In the area of the arts, things were very different. In the art of the Achaemenids numerous influences are detected, but so integrated that they ended up giving birth to a national art.

Religious aspect: “Thus spoke Zarathustra”

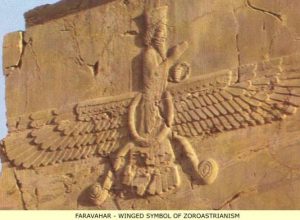

In contrast to other empires, the Persians were tolerant of the religions of the dominated. In no place did they impose by force their religion or their gods. This is not due to their political ability, but to their religious conceptions. This is found gathered in the Avesta, the sacred book with gathers the teachings of the preacher Zoroaster or Zarathustra.

Zoroaster was the founder of the religion called Zoroastrianism of Mazda-ism. According to the legend, he received revelations from the great god Ahura Mazda, supreme, immaterial god, creator of the universe.

According to Zoroaster, two spirits existed in conflict: that of good, in service to Ahura Mazda, and that of evil, or which fights. The spirit of good, called Hormuz, represented life, truth, and justice. It was the world of the great god, with light and happiness. The spirit of evil represented death and lies. It was the world of darkness, led by Ahriman.

Man also participates in this struggle, according to his good or bad behavior. If it is in accordance with the spirit of good, he is rewarded in his above-ground life. This religion with certain monotheistic characteristics of a supreme god was accepted especially by the leading classes of the empire. Although the greater part of the population kept Ahura-Mazda in the superior position, they surrounded him with other inferior divinities, personified by the natural forces.

As we see, this religion had a marked moral content: man can and should choose between good and evil. Man should work, collaborate with the community, have many children, promote a quiet social coexistence. Worship was essentially the fulfillment of these duties, complemented with the veneration of fire. Zoroaster condemned offerings and bloody sacrifices, although the magi practiced them anyway.

The Mazdaist religion remained as the national religion until the 7th Century A.D., in which Iran was conquered by the Muslims and these imposed their religion, Islam. In the present this religious practice is preserved in the area of Bombay, in India, thanks to the Mazdaists who fled from the Muslim persecution.

Agriculture and Livestock

As in the other countries of the ancient Orient, the problem of water was crucial in the Persian Empire, with the exception of a few rare, privileged regions. Because of this, the peasants put together perfected systems of irrigation. Canals were excavated for the conduction of water, as well as wells and subterranean galleries, similar to the “qanats” of present-day Iran, to avoid, in the aridest regions, excessive evaporation.

In this way, the ground was revalued and grains like barley and wheat were cultivated above anything else, but also vineyards, as on the great occasions, especially in the era of their decay, the Persians consumed wine and other alcoholic drinks. On the other hand, the raised great flocks of horses and bovines, as well as donkeys and camels.

Horses were nearly all for riding, while donkeys and oxen were used for working the fields: making the mill wheels turn, or pulling wooden plows, equipped with a metal point, which served for tilling. The lands belonged, sometimes, to independent peasants, who, in cooperative groups, worked the lands of various families. The other lands belonged to the nobility, who ceded its operation to settlers, being left with part of the harvest.

Because of the lack of water and vegetation in this country burned by the sun, the Persians gave great importance to gardens for recreation, whose supreme luxury consisted in being scored with innumerable small streams, sprinkled by fountains and full of flowers.

The tradition of gardens has been conserved, on the other hand, in this area of the world, not only throughout all of the ancient times, but also during the Middle Ages, in Muslim Persia, and in modern times. Important hunting preserves, favorite sport of the nobility, starting with the king, were likewise available, in the form of parks: they called them “paradises.” Although agriculture and the art of gardens had developed much in the empire of Darius, the same would not happen with industrial work. There were almost no artisans, as the Persians preferred to buy the manufactured products from their neighbors.

It is not impossible that religious factors originated this lack of interest in activities which produce the transformation of material. Commerce flourished, especially in the interior, thanks to the important system of roads. In addition to the royal road from Sardis to Susa, numerous highways crossed the Empire in all directions, as much in the Asian interior as in Afghanistan or in the Indian Provinces.

Of course, their trace had been made, above all, to satisfy the political, military and administrative necessities of the Empire, but they were also made use of for commerce as well. On these routes, whose distances were measured in Parasangs (each Parasang was equivalent to a little more than five kilometers), lodgings had been established which, according to Herodotus, impenitent traveler, were excellent.

The roads had, in addition, the advantage of being safe, a very rare thing in ancient times. “The royal roads, which they traverse continually, united the most distant capitals of the Empire, Sardis and Susa (2,500 km.), in a record time of approximately a week.”

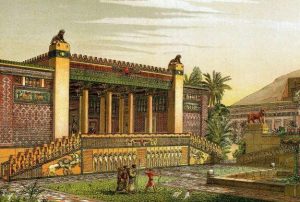

Persian Art: An art for the monarchy

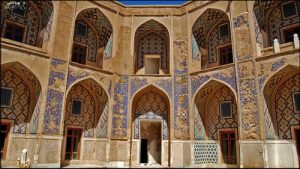

We cannot state that a Persian art existed, strictly speaking. In reality the artistic production was a conjunction of elements belonging to the different subdued cultures. For example, from the Egyptians they the construction of hypogeums; from Mesopotamia, the use of brick, the figures of winged bulls and the custom of erecting palaces on elevated platforms; from Greece, the harmony and slenderness of certain constructive elements.

By reason of the characteristics of the Achaemenid religion, they did not build temples dedicated to the worship of their god, nor was it materialized in relieves or sculptures. For this reason, the art of the Iranians was dedicated exclusively to the monarchy.

Persian Architecture

The Persians dedicated themselves fundamentally to the construction of palaces with monumental characteristics. The most important were those of Susa and Persepolis.

Among the diverse locales which made up these magnificent constructions, the most important was the Audience Hall. There could be found the throne of the king, and it was the place where he presented himself in public.

The walls of these buildings were of bricks, combined with elements of carved stone (frames for doors and windows, columns).

The columns, which supported the roofs, were of great height, of fluted shape, and at their highest end were found capitals formed of two bulls’ heads worked in stone, where the beams were supported.

Sculpture

The Persians utilized bas-reliefs in the Mesopotamian manner. Monumental inscriptions were dedicated to the king, carved into the sides of mountains, where military successes were related. They also sculpted the facades of the tombs dedicated to the kings, likening them to the fronts of palaces.

Legacy of the Ancient Persian Civilization

Politics: The idea of a universal empire, an objective recreated by many nations in the course of human history.

Economy: Generalization of the use of money in commercial transactions.

Intellectual Life: The idea of the struggle between good and evil and man’s freedom of choice in choosing between the two.

Ethics: Tolerance towards conquered peoples.