Ancient Rome made its way from a small handful of villages in the ancient times to becoming the city-state that controlled Italy and which, in the end, became the luxurious capital of a vast empire.

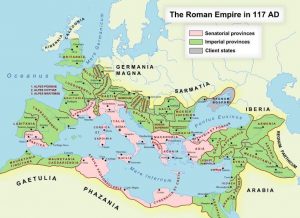

Under the command of great generals like Julius Caesar, its disciplined troops defeated almost all of its enemies. Around the 1st century AD, Rome ruled the ancient kingdoms of Egypt, Syria, Greece, part of Africa and even the wild barbarian lands of Europe.

Ancient Rome

Contents

Ancient Rome: Geographical Setting

Rome is a city and the capital of both Italy and the region of Lazio, and the province of Rome, located on the Tiber River, in the central part of the country, near the Tyrrhenian Sea.

The Urban Landscape of the First Roman Period

According to tradition, Rome was founded in 753 BC, on one of the Seven Hills (a term used for centuries to refer to the Capitoline, Quirinal, Viminal, Esquiline, Celia, Aventine and Palatine hills surrounding the old community). However, archaeological findings indicate that human settlement of the territory dates, at least, from 1000 BC. The Capitoline Hill was the seat of the Roman government for a long time, and the Palatine Hill had magnificent buildings, such as the Palace of the Flavians, built by the Roman emperor Domitian. As a result of building over the centuries, the hills of the adjacent plain can hardly be distinguished. Other Roman hills are the Pincian (Pincio) and the Janiculum.

Currently, Rome is divided into two basic regions: the interior, delimited by the Aurelian Walls, constructed at the end of the 3rd century AD to surround the area around the Seven Hills; and the outside, characterized by its outlying neighborhoods. The historic center is a small area almost entirely located on the east bank of the Tiber. The monuments of Rome’s glorious past are found within the historic center. The layout of the streets reflects its long and complex history; the Via del Corso runs through much of the historic center from Piazza Venezia, the geographical center of Rome, to Piazza del Popolo, at the bottom of the Pincian Hill. It was used from the Middle Ages as a race track.

Roman Presence

Roman presence in the peninsula followed the Greek commercial colony routes. However, the Roman presence began with a fight between Rome and Carthage for control over the Western Mediterranean during the 2nd century BC. In any case, it was during this period that the Iberian Peninsula was introduced as an entity in the international political scene at the time, and since then it has become a coveted strategic objective, due to its peculiar geographical situation between the Atlantic and the Mediterranean, and the mining and agricultural wealth in its south.

Chronology of Ancient Rome

The Roman penetration and subsequent conquest of the Iberian Peninsula spans a prolonged period from 218 to 19 BC. The most significant dates of this period are:

209 BC: Hannibal’s army’s decline in Italy and the beginning of the great Roman conquest of Spain. They annex the country and divide it into two provinces: Hispania Citerior and Hispania Ulterior.

From 143 to 139 BC: Viriatus and the Lusitanians fight against the Roman legions.

133 BC: The inhabitants of Numantia choose burning to death in the city’s flames over surrendering to Scipio Aemilianus.

27 BC: The Romans pacify the peninsula once and for all and divide it into provinces: Hispania Tarroconensis, Hispania Baetica and Lusitania. The Roman presence in Hispania lasted seven centuries, during which the peninsula’s most important borders were drawn up in relation to other European countries. However, the Romans not only passed on territorial administration, but also left a legacy of social and cultural references, such as family, language, law and municipal government, whose assimilation definitively placed the peninsula in the Greco-Roman world at first, and then later in the Judeo-Christian world.

98 AD: The beginning of Trajan’s reign, the first Roman emperor of Spanish origin.

264 AD: The Franks and the Suebi invade the country and temporarily occupy Tarragona.

411 AD: The barbarian tribes sign an alliance with Rome that allows them to establish military colonies within the empire.

568-586 AD: The Visigothic king Liuvigild expels imperial officials and tries to unify the peninsula. The end of the Roman Empire in Spain.

Ancient History: The Roman age

From the 3rd century BC until the 5th century AD.

The Roman Conquest

The Roman presence in the Iberian Peninsula was due to the development of its struggle with Carthage for control over the Mediterranean Sea. After the decisive victory of the Roman proconsul Scipio in Ilipa (Alcala del Rio) in 206 BC, over the Carthaginian army, the Romans advanced to the southern end of the peninsula and took Gades (Cadiz). Thus, the Carthaginians fled to the Balearics, where they tried to raise the Ligurians and Gauls against the Romans. With this, the Carthaginian rule in the territories of modern day Spain ended.

The Roman conquest of Hispania began in 218 BC with the Battle of Cissa and the occupation of Tarraco (Tarragona) by Gnaeus Cornelius Scipio Calvus’ troops. He came to the Iberian Peninsula to cut off the supply of men and money needed by the Carthaginians, who were commanded by Hannibal during his assault on Italy. But after expelling the Carthaginians from Hispanic territory, Rome breached its commitment to evacuate the area and transformed it into a province in 206 BC. As a result, the tribes previously allied with Rome rebelled on several occasions but were defeated by Scipio, who imposed harsh conditions of peace.

The Roman conquest of Hispania began in 218 BC with the Battle of Cissa and the occupation of Tarraco (Tarragona) by Gnaeus Cornelius Scipio Calvus’ troops. He came to the Iberian Peninsula to cut off the supply of men and money needed by the Carthaginians, who were commanded by Hannibal during his assault on Italy. But after expelling the Carthaginians from Hispanic territory, Rome breached its commitment to evacuate the area and transformed it into a province in 206 BC. As a result, the tribes previously allied with Rome rebelled on several occasions but were defeated by Scipio, who imposed harsh conditions of peace.

Roman Consolidation

In 197 BC, the Iberian Peninsula was divided into two provinces: Hispania Citerior and Hispania Ulterior, fronted by two proconsuls.

Between the years 197 and 179 BC there was a series of uprisings by various Iberian peoples. This led to the Roman Senate sending large numbers of troops to quell the rebellions, pacifying Hispania Citerior in 194 BC after capturing Jaca. However, in Hispania Ulterior, after the Iberian peoples were defeated in 178 BC, the land was divided up in order to settle the Hispanic nomads. This extended the area of effective Roman rule without great resistance, and with the Numantian pact, they also gained a period of relative peace.

After the Lusitanian (155-136 BC) and Celtiberian Wars (153-133 BC), Roman power in Hispania was reasserted. However, in 83 BC a period of civil wars began, which ended in 45 BC. In addition, wars with the Cantabrians, Asturians, and Vascones took place in this period, which were most violent with Augustus’s attacks between the years 25 and 19 BC.

The Cities in Ancient Rome

The political organization of the cities depended on whether they were natives or Romans.

Native Cities

There could be, in turn, in two types of native cities: stipendiary or free.

The stipendiary native cities paid a type of type tax or tribute, maintained their own law and minted currency. Its inhabitants, who were free, owned the land. These types of cities were generally those that had been defeated by Rome after resistance.

Meanwhile, the free native cities were also treated differently; free, federated cities, of which there were few, had great autonomy and maintained their own organization and administration. The inhabitants were exempt from serving in the army, but they had to give aid to the mother country in case of war. Non-federated free cities enjoyed the same conditions, not by express agreement, but by concession. Finally, there were the immune cities, which were exempt from taxes.

Roman Cities

Roman cities were founded to take in Roman citizens who came to the peninsular.

These cities had a political-administrative regime similar to the actual Latin cities. Sometimes military encampments became cities (as was the case in Leon, Astorga and Pamplona).

Concession of Roman Citizenship

Later, in 212 AD, Roman citizenship was granted to the entire Empire and, therefore, also to Hispania, although indigenous law continued to be used in rural areas. Political administration, after various modifications, was finally settled in 293 AD thanks to Diocletian, who divided the entire Empire into prefectures, dioceses, and provinces. The diocese of Spain was part of the prefecture of Gaul, and included the provinces of Hispania Baetica, Lusitania, Hispania Gallaecia, Hispania Tarraconensis, Hispania Carthaginensis, Mauretania Tingitana and Hispania Balearica.

Agriculture

Crops of wheat, grapevines and olives stood out among agricultural products. Also important was the production of linen, straw and cotton. Two or three field fallow and fertilizers were introduced, making the use of the plow widespread.

Mining

In regards to mining, the extraction of lead in Cartagena, copper in Río Tinto (province of Huelva), mercury in Almaden, gold in Beatica and Asturias, and iron in Moncayo, Cantabria and Toledo should be noted. The miners were slaves.

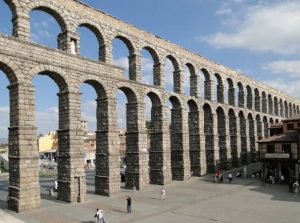

Large Works

In a different vein, the construction of important terrestrial communication lines and public works such as aqueducts, thermal baths and administrative, religious and recreational buildings is worth mentioning. A particularly interesting example is found in the Green Lung of Huelva, the subterranean Roman aqueduct in Cabezos del Conquero.

Also great were the cultural works of three Cordobans: father Seneca the Elder and son Seneca the Younger, and Lucan, who left behind important literary and philosophical works.

History of Ancient Rome

According to legend, the city was founded by Romulus (and his brother Remus, according to some versions) in 753 BC. Although archaeological evidence indicates that humans previously existed in the area, an extensive human settlement could well date back to this date. Signs of an Iron Age village from the mid-8th century BC, have been found on the Palatine Hill. The legend of the Rape of the Sabines and the subsequent fusion of Romans and Sabines, are also supported by archaeological remains.

Ancient Rome was a kingdom based on two classes, the patricians (nobles) and the plebeians, who lacked civil and political rights. The Senate, or Council of Elders, elected the monarchs and limited their power.

The Roman Kingdom

(C. 753-510 BC)

A period of Roman history where many legends and symbolic histories converge, about which historians of this period have created incomplete accounts with respect to its origin and evolution. The decadence of the monarchic period was often contrasted with the idealism of the Roman Republic.

According to legend, Rome was founded in 753 BC by Romulus and Remus, twin sons of Rea Silvia, a Vestal Virgin, and daughter of Numitor, the king of Alba Longa, a nearby town in ancient Lazio. An older tradition traces the Romans’ ancestry to the Trojans and their leader Aeneas, whose son Ascanius was the founder and first king of Alba Longa. The tales of Romulus’s reign highlight the Rape of the Sabines and the war against them, led by Titus Tatius. They also highlight the union of the Latin and Sabine peoples. The reference to the three peoples (the Ramnes, the Tities, and Luceres) in the legend of Romulus, who were part of a new state, suggests that Rome was created by a cultural fusion of Latins, Sabines and Etruscans.

The seven kings of the monarchical period and the dates traditionally assigned to them are: Romulus (753-715 BC); Numa Pompilius (715-676 or 672 BC), who was credited with introducing many religious customs; Tullus Hostilius (673-641 BC), a warlike king who destroyed Alba Longa and fought against the Sabines; Ancus Marcius (c. 641-616 BC), who is said to have built the port of Ostia and captured many Latin cities, transferring their inhabitants to Rome; Lucius Tarquinius Priscus (616-578 BC), famous for his great military exploits against neighboring towns as much as for the construction of public buildings in Rome; Servius Tullius (578-534 BC), famous for his new constitutions and for widening the city limits; and Lucius Tarquinius Superbus (534-510 BC), the seventh and last king, overthrown when his son raped Lucretia, the wife of a relative. Tarquinius was banished, and the attempts of the Etruscan or Latin cities to restore him to the Roman throne were unsuccessful.

Although the names, dates, and events of the royal period are believed to be fiction, there is solid evidence of the existence of an ancient monarchy, the growth of Rome, its struggles with neighboring peoples, the Etruscan conquest of Rome and the establishment of a dynasty of Etruscan kings, symbolized by the rule of the Tarquins, their deposition and the abolition of the monarchy. The existence of a certain social and political organization, such as the division of the inhabitants in two classes, is also probable. The patricians, who alone possessed political rights and organized the populus or people, and their subordinates, known as clients and plebeians, who initially had no political status. The rex or king, chosen by the Senate (Senatus) or Council of Elders (patres), who were patricians, occupied the position for life. They were responsible for assembling the populus to war and directing the army in battle. In parades, he was preceded by officials, known as lictors, who carried fasces, a symbol of power and punishment. He was also the supreme judge in all civil and criminal disputes. The Senate only gave advice when the king decided to consult it, although its members had great moral authority, since their positions were also for life. At first only the patricians could carry arms in defense of the State. It seems that there was a major military reform, known as the Servian reform, as it possibly took place during the mandate of Servius Tullius, in the 6th century BC.

By this time, the plebeians could acquire property and, according to the reform, all owners, both patricians and plebeians, were obliged to serve in the army, where they were designated a rank according to their wealth. This plan, although initially serving a purely military purpose, paved the way for the great political struggle between the patricians and plebeians during the first centuries of the Roman Republic.

The Roman Republic

A period of Roman history characterized by the republican regime as the method of government, which lasts from 510 BC, when the monarchy ended with the expulsion of the last king, Lucius Tarquinius Superbus, to 27 BC when the Empire began.

Conquest of the Italian peninsula (510-264 BC)

In place of the king, all citizens annually elected two magistrates, known as praetors (or military leaders) who later received the title of consuls. Dual participation in supreme power and the limitation of one year of magistrate rule avoided the danger of autocracy. The character of the Senate, an advisory body that already existed during the monarchy, was changed with the admission of plebeians, known as conscripti. Since then senators were officially called patres conscripti (conscript fathers). Initially, only patricians could occupy magistrate positions, but the displeasure of the plebs started a violent struggle between the two social groups and the progressive disappearance of the social and political discrimination to which plebeians had been subjected.

In 494 BC, the plebeians’ secession (withdrawal) to the Aventine Hill (one of the Seven Hills of Rome) forced the patrician classes to allow the tribuni plebis institution (Tribune of the Plebs), who were elected annually by the Concilium Plebis (Plebeian Council), as plebeian representatives to uphold their interests. They had a right to veto the acts of the patrician magistrates and in reality acted as the leaders of the plebeians in conflicts with the patricians. The formation of a decemvirate ( a , committee of ten men) in 451 BC resulted in the writing of a legal code. In 455 BC the Canuleian Law declared marriages between patricians and plebeians legally valid. Under the Licinian Rogations (367 BC) one of the two consuls had to be plebeian. The rest of the magistrates gradually became available to the plebeians, including the dictatorship (356 BC), an unusual magistracy chosen in times of great danger, the rank of censor (350 BC), the position of praetor (337 BC) and the pontifical and augural college magistrates (300 BC).

These political changes gave way to a new aristocracy composed of prosperous patricians and plebeians and made admission into the Senate an almost a hereditary privilege for these families. The Senate, which had originally had little administrative power, became a fundamental body of power; it declared war and brought peace, established alliances with other foreign states, decided on the founding of colonies and managed the finances of the State.

Although the rise of these nobles put an end to the disputes between the two social groups, the position of the poorest plebeian families did not improve and the sharp contrast between the conditions of the rich and the poor gave rise to struggles between the aristocratic and popular parties at the end of the Republic.

Rome adopted an expansionist foreign policy during this period. Before the dissolution of the monarchy, Rome was already the predominant power in Lazio. Aided by their allies, the Romans fought against the Etruscans, Volsci, and Aequi.

Between 449 and 390 BC Rome was especially aggressive. The conquest of the Etruscan city of Veii in 396 by the soldier and politician Marcus Furius Camillus signaled the beginning of the decline of Etruscan civilization. Other Etruscan cities hastened to broker peace and in the middle of the 4th century BC, Roman garrisons had been established in the south of Etruria, where a large number of Roman colonists had settled. Victories over the Volsci, Latins and Hernici, gave Rome control of central Italy and also brought conflict with the Samnites of southern Italy, who were defeated after the so-called Samnite Wars (343-290 BC). Rome repressed a Latin and Volscian revolt and in 338 BC, the Latin League (a confederation cities in Lazio established many years ago), was dissolved. The powerful coalitions formed by the Etruscans, Umbrians and Gauls in the north, and the Lucanians and Samnites in the south, threatened Roman power were defeated; first the northern confederacy in 283 BC and the south shortly after that. In 281 BC the Greek colony of Taranto requested aid from Pyrrhus, the King of Epirus, against Rome. His campaigns in Italy and Sicily (280-276 BC) were unsuccessful and he returned to Greece. Over the next ten years, Rome finalized its rule in the south of Italy and in this way managed to impose its power over the entire Italian peninsula up to the Arno and Rubicon rivers.

External Dominance

Rome began its struggle with Carthage in 264 BC for control over the Mediterranean Sea. At the time, Carthage was the world’s dominant sea power and ruled the central and western Mediterranean absolutely, while Rome dominated over the Italian peninsula.

The Punic and Macedonian Wars

Punic Wars

1. The first of the Punic Wars (264-241 BC) was mainly over the possession of Sicily and led to the birth of Rome as a great naval power. With the support of Hiero II, the tyrant of Syracuse, the Romans conquered Agrigento, and its newly created fleet, under the command of the consul Gaius Duilius, defeated the Carthaginians in the Battle of Mylae (260 BC). The continuation of the war in Africa ended with the defeat and capture of the Roman general Marcus Atilius Regulus. After a series of defeats at sea, the Romans won a great naval victory in 242 BC in the Aegates Islands, west of Sicily. The war ended in 241 BC with the transfer of the Carthaginian area of Sicily to Rome, which became a Roman province, the first foreign Roman possession. Shortly afterward, Sardinia and Corsica were taken from Carthage and annexed as provinces.

As Rome had equal strength with its naval forces, Carthage prepared for the resumption of hostilities by acquiring possessions in Hispania. Under the command of Hamilcar Barca, Carthage occupied the Iberian Peninsula up to the Tagus River. Hasdrubal, Hamilcar’s son-in-law, continued the subjection of this territory until his death (221 BC). Between 221 BC and 219 BC, the new Carthaginian general Hannibal, son of Hamilcar, extended Carthaginian conquests up to the Ebro River.

2. The Second Punic War (218-201 BC) began when Hannibal invaded the Italian peninsula after leaving his camps in the Iberian Peninsula and crossing the Alps with elephants. He defeated the Romans in consecutive battles and ravaged much of southern Italy for several years, but he had to return to Africa to confront Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus. Scipio Africanus had invaded Carthage and won a decisive victory over Hannibal in the Battle of Zama (202 BC). As a result of this battle, Carthage had to surrender its fleet, cede Hispania and its possessions in the Mediterranean islands to Rome, and pay an enormous amount of compensation. From this point, Rome gained complete control over the western Mediterranean.

Under their rule, Roman treatment of the Italian communities became stricter, while the Greek cities in southern Italy, which had supported Hannibal, became Roman colonies. Rome continued to extend its power to the north; between 201 and 196 BC, the Celts of the Po River valley were subdued and their territory Latinized, although they were denied Roman citizenship. Corsica and Sardinia were subdued and Hispania was occupied by the military, which led to the first standing Roman armies.

During the 3rd and 2nd centuries BC, Rome had to tackle Macedonia for control over the Aegean Sea in the so-called Macedonian Wars. The Macedonian forces were led during the first two wars by Philip V, who was finally defeated in 197 BC. With the help of the southern Greek cities, the Romans continued against Antiochus III the Great, King of Syria, whom they defeated at Magnesia in 190 BC, and forced to surrender his possessions in Europe and Asia Minor. Philip’s son and successor, Perseus (c. 212-166 BC) continued the resistance against the Romans, which led to the outbreak of the Third Macedonian War.

In 168 BC, his army was put to flight at Pydna by general Lucius Aemilius Paullus (229-160 BC). Macedonia became a Roman province in 146 BC. That same year, the final Achaean League revolt in Greece against Roman rule ended with the conquest and destruction of Corinth.

3. Rome finally had to fight the Third Punic War (149-146 BC), which ended when Publius Cornelius Scipio Aemilianus conquered and destroyed Carthage, which from then on was part of the Roman province of Africa. The conquest of Numantia in 133 BC ended a series of campaigns in the Iberian Peninsula. In that same year, Rome also assimilated the Kingdom of Pergamon after the death of its last ruler, Attalus III; shortly afterward this territory became part of the province of Asia.

In 131 years, Rome had created an empire that ruled the Mediterranean from Syria to Hispania. As a result of these conquests the Romans came into contact with the Greeks, first in southern Italy and Sicily, and later in the east, and adopted much of their culture, art, literature, philosophy and religion. The development of Latin literature began in 240 BC with the translation and adaptation of epic poetry and Greek dramas. In 155 BC, Greek philosophy schools were established in Rome.

Internal Conflicts

Rome’s internal problems began with the acquisition of its vast territories. Some extremely wealthy plebeian families allied themselves with the old patrician families to exclude the other citizens from the highest magistrates and the Senate. This aristocratic ruling class (optimates) became increasingly arrogant and prone to extravagance, losing their ancestors’ high levels of morality and integrity. The gradual disappearance of peasants, caused by the creation of large agrarian estates, a system of slavery and the wars’ devastation of the countryside, led to the development of an urban proletariat whose political opinion was not taken into account. Conflict between the aristocratic and popular parties was inevitable. Attempts by the plebeian tribune Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus and his brother Gaius Sempronius Gracchus to alleviate the poorest citizens’ situation with an agrarian reform and grain distribution ended in revolts in which both brothers died.

Roman territorial extension continued. In 106 BC Jugurtha, the King of Numidia, was dethroned by the consul Gaius Marius with the help of Sulla. This victory increased Roman military prestige, consolidated after Marius’s defeat of the Cimbri and the Teutones in southern Gaul and northern Italy after his return from Africa.

The Italic communities allied with Rome felt that their burdens increased while their privileges diminished, and demanded Rome share the benefits of the conquests to which they had contributed. The tribune Marcus Livius Drusus tried to reconcile the poor with a series of legal reforms on land possession and grain distribution, and the Italian armies with the promise of the concession of Roman citizenship. His assassination was followed, a year later, by an Italic army revolt, whose aim was to create a new Italic state governed according to the Roman constitution’s guidelines. After the so-called Social War, the Italic peoples (mainly the Marsi and Samnites) were finally defeated, but they had achieved full Roman citizenship.

Rome’s internal problems continued. During the war with Mithridates VI, the King of Pontus, conflict between Gaius Marius, the spokesman of the popular party, and Sulla, leader of the optimates (aristocratic party), exploded over who should lead the military expedition. Sulla marched on Rome with the legions he had commanded during the Social War, and Roman legions entered the city for the first time. Marius’s later flight and the tribune Publius Sulpicius Rufus’s execution made way to Sulla imposing arbitrary measures and setting off against Mithridates in 87 BC. In Sulla’s absence, Lucius Cornelius Cinna, the leader of the popular party and a fierce opponent of his, wanted to introduce the reforms initially proposed by Rufus, but he was expelled from Rome. He gathered the legions around him in Campania and with Marius (who had returned from Africa) he entered Rome. They shared the consulate in 86 BC, but Marius died soon after, and then a retaliatory massacre of senators and patricians began. Cinna remained in power until 83 BC, when Sulla returned from Asia Minor with 40,000 men, marched to Rome and defeated the popular party. After this, the republican constitution was at the mercy of whoever had the strongest military support. Sulla suppressed his enemies by outlawing them, drafting and placing a list of important men who were declared public enemies and outlaws in the forum. He also confiscated the lands of his political opponents, which he granted to his legions’ veterans, who were usually neglected or abandoned. Rome’s rich agricultural economy declined, and the city had to import much of its food, especially from Africa, which became Rome’s largest grain supplier.

The Ascension of Caesar

In 67 BC, Pompey, a Roman military leader and politician who had fought against Marius’s supporters in Africa, Sicily and Hispania, put an end to piracy in the Mediterranean and was in charge of leading the war against Mithridates. Meanwhile, his rival Gaius Julius Caesar, taking advantage of his absence, acquired great prestige as the leader of the popular party by claiming the rehabilitation of the reviled Marius and Cinna, begging for their children’s mercy and bringing Sulla’s corrupt followers to justice.

Caesar found a helpful ally in Marcus Licinius Crassus, a man of great wealth. Nevertheless, Caesar provoked opposition from the middle classes when he was involved in the Catilinarian conspiracy in 63 BC. Two years later, Pompey returned victorious from the East, demanded that the Senate ratify the measures he had adopted in Asia Minor and granted land to his veterans. His requests were met with strong opposition until Caesar opted for reconciliation; Pompey, Crassus, and Caesar made up the so-called first triumvirate in 60 BC.

The triumvirate managed to obtain the consulate for Caesar and satisfy Pompey’s demands. The equestrians (knights), many of whom were wealthy members of the mercantile class, were placated at the expense of the Senate and an agrarian reform was carried out that allowed Caesar to reward his troops. However, his greater success was gaining the military command of Cisalpine Gaul, Illyria and later Transalpine Gaul, where he achieved important military conquests. In 55 BC the triumvirs renewed their alliance and Caesar extended his command in Gaul for five more years. Pompey and Crassus were elected consuls in 55 BC, and the following year Pompey received command over the two provinces in Hispania, and Crassus the one in Syria. The death of the latter (53 BC) sparked conflict between Caesar and Pompey. Rome fell into a period of disorder until the Senate incited Pompey to remain in Rome, entrusting his province to legates. It appointed him sole consul in 52 BC and supported him in his fight against Caesar.

In order to prevent Caesar from appearing as a candidate for the consulate in 49 BC, the Senate demanded that he leave his military command. Caesar refused, and in 49 BC he crossed the Rubicon River from Cisalpine Gaul and took Rome, forcing Pompey and the aristocratic leaders to retreat to Greece. Caesar’s victory meant the introduction of economic and administrative reforms in an attempt to overcome corruption and restore prosperity to Rome. Caesar continued the war against Pompey, defeating his armies in Hispania and crossing over to Greece, where he fought the decisive Battle of Pharsalus at the beginning of the year 48 BC. After his victory, Caesar returned to Rome as a dictator for life.

Pompey was murdered shortly afterward in Egypt, but the war against his supporters continued until with their definitive defeat at Munda (in Baetica, Hispania) in 45 BC. Caesar was then appointed consul for a period of ten years.

Caesar gained the enmity of the aristocracy by ignoring republican traditions and was assassinated on the 15th of March in 44 BC. Marcus Tullius Cicero attempted to restore the Republic’s old constitution, but Mark Antony, who had been appointed consul with Caesar, joined Marcus Aemilius Lepidus and Caesar’s nephew, Octavian (later Emperor Augustus) to form the second triumvirate. The triumvirs began their mandate by proscribing and murdering their republican opponents, including Cicero. In 42 BC, Octavian and Mark Antony defeated the forces of Marcus Brutus and Gaius Cassius Longinus, two of Caesar’s assassins, in Philippi in northern Greece. Later the three divided control of the Empire: Octavian kept Italy and the West, Mark Antony the East and Lepidus Africa. Shortly after taking control of his eastern sphere, Mark Antony, succumbed to the charms of the Queen of Egypt, Cleopatra VII, and planned to create an independent Eastern empire with her. Lepidus, called to Sicily by Octavian to help him in the war against Sextus Pompey (son of Pompey the Great), tried to conquer Sicily for himself, so he was deprived of his province and separated from the triumvirate. The death of Sextus Pompey, after the destruction of his fleet, left Octavian, who had reinforced his position in the West, alone facing Mark Antony as a rival. After the Battle of Actium (31 BC) and the later suicides of Mark Antony and Cleopatra, Octavian gained control of the East (29 BC) and consequently total supremacy over Roman territory.

Despite successive civil wars, Latin literature underwent a remarkable development during the so-called ‘Ciceronian Age’ (70-43 BC). It was the first part of what was known as the golden age of Roman literature. The next period (43 BC-14 AD) is known as the ‘Augustan Age’. Caesar and Cicero brought Latin prose to new heights, Terence was one of the most brilliant playwrights of the age and Catullus and Lucretius stood out for their brilliant poetry.

The Roman Empire

A period of Roman history characterized by a political regime dominated by an emperor that spans from the moment Octavian received the title of “Augustus” (27 BC) until the dissolution of the Western Roman Empire (476 AD).

Augustus and the Julio-Claudian dynasty

The Empire succeeded the Roman Republic and Augustus, as the first citizen, maintained the republican constitution until 23 BC, in which royal authority covered tribunician power and the military empire. The Senate retained control of Rome, the Italian peninsula and the more Romanized and peaceful provinces. The border provinces, where stable barracks of legions were needed, were governed by legates, who were named and directly controlled by Augustus. The corruption and extortion that had characterized the Roman provincial administration over the last century of the Republic was not tolerated, which benefited the provinces especially.

Augustus introduced numerous social reforms, including those that hoped to restore the moral traditions of the Roman people and the integrity of marriage; he tried to combat the promiscuous customs of the age and revive old religious festivals. He embellished Rome with temples, basilicas, and porticoes in what looked like the birth of an era of peace and prosperity. This period represents the culmination of the golden age of Latin literature, in which the poetic works of Virgil, Horace and Ovid, and Livy’s monumental prose, History of Rome, stand out.

With the establishment of an imperial system of government, the history of Rome was largely identified with the reigns of each of the emperors. Emperor Tiberius, the successor of his stepfather Augustus from 14 AD, was a competent manager, and an object of general discontent and suspicion; relying on military power, he maintained the Praetorian Guard in Rome (the only troops allowed in the capital), always ready for his call. He was succeeded by the tyrannically and mentally unstable Caligula (27-41). Upon his death, the imperial title passed to Claudius, whose mandate contemplated the conquest of Britain, and continued the public works and administrative reforms initiated by Caesar and Augustus. His adoptive son Nero began his government under the wise advice and counsel of the philosopher Seneca the Younger and Sextus Afranius Burrus, the prefect of the Praetorian Guard. However, his later abuses of power led to his overthrow and suicide in 68 AD, which marked the end of the Julio-Claudian dynasty.

The Flavian and Antonine dynasties (69-192)

The brief reigns of Galba, Otto, and Vitellius in 68 and 69 AD were followed by that of Vespasian, who together with his sons, the emperors Titus and Domitian, made up the Flavian dynasty. They revived the simplicity of the court at the beginning of the Empire and attempted to restore the authority of the Senate and promote the welfare of the people. It was during Titus’s reign that Vesuvius erupted, which devastated the area south of Naples where the cities of Herculaneum and Pompeii were. Although literature flourished during Domitian’s reign, he became a cruel person and a tyrannical ruler in his final years. This period of terror only ended with his murder.

Nerva (96-98) was the first of the so-called five good emperors along with Trajan, Hadrian, Antoninus Pius and Marcus Aurelius. Each of them was chosen and legally adopted by his predecessor according to their skill and integrity. Trajan carried out campaigns against the Dacians, Armenians and Parthians, allowing the Empire to reach its greatest territorial expanse; he was also noted for his excellent management. The satirical writer Juvenal, the orator and writer Pliny the Younger and the historian Tacitus lived during Trajan’s reign. Hadrian’s 21 years of rule were also a period of peace and prosperity; after yielding some of the most eastern territories, Hadrian consolidated the rest of the Empire and stabilized its borders. The reign of his successor, Antoninus Pius was equally marked by order and peace. The incursions of various migrant peoples into various areas of the Empire shook the reign of the next emperor, the stoic philosopher Marcus Aurelius, who ruled with Lucius Verus until his death. Marcus Aurelius was succeeded by his decadent son Commodus, considered one of the most bloodthirsty and promiscuous tyrants in history. He was assassinated in 192 and the Antonine dynasty died with him.

Decline and fall of the Empire

The brief reigns of Pertinax (193) and Didius Julianus were followed by Lucius Septimius Severus (193-211), the first emperor of the brief Severan dynasty. The emperors of this lineage were: Caracalla, Elagabalus (218-222) and Severus Alexander (222-235). Septimius Severus was a skilled ruler; Caracalla was famous for his brutality, and Elagabalus for his corruption. It stands out that Caracalla granted Roman citizenship to all free men of the Roman Empire in 212 in order to be able to tax them, as only citizens were subjected to tax. Severus Alexander stood out for his justice and wisdom.

The period following the death of Severus Alexander was one of great confusion. Of the 12 emperors who governed over the next 33 years, almost all of them died violently, usually killed by the army, who’d also enthroned them. The Illyrian emperors, natives of Dalmatia, succeeded in developing a brief period of peace and prosperity. This new dynasty included Claudius Gothicus, who defeated the Goths, and Aurelian, who between 270 and 275 defeated the Goths, Germans and Zenobia, the Queen of Palmyra, who had occupied Egypt and Asia Minor, restoring the unity of the Empire for some time. Aurelian was followed by a series of relatively insignificant emperors until Diocletian ascended to the throne in 284.

A capable ruler, Diocletian carried out a good amount of social, economic and political reforms. He eliminated the economic and political privileges that Rome and Italy enjoyed at the expense of the provinces, and tried to regulate rising inflation through controlling food prices and other basic commodities. As well as introducing a worker’s maximum wage, he instituted a new system of government in which he and Maximian shared the title of ‘Augustus’ in order to establish fairer administration throughout the Empire. His powers were reinforced by the appointment of two Caesars, Galerius, and Constantius, thus establishing the tetrarchy regime (two Augusti and two Caesars). Diocletian controlled Thrace, Egypt, and Asia, while his Caesar Galerius ruled the Danubian provinces. Maximian ran Italy and Africa and his Caesar Constantius ruled Hispania, Gaul, and Britannia. The tetrarchy created a more solid administrative machinery but increased the already large governmental bureaucracy with four imperial sectors and corresponding officials, which put a huge financial burden on the limited imperial resources.

Diocletian and Maximian abdicated in 305 and left the two new Caesars caught up in a civil war, which did not end until the ascension of Constantine the Great in 312. Constantine, who had previously been Caesar in Britain, defeated his rivals in the struggle for power and reunited the Western Empire under his command. After defeating Licinius, the Eastern emperor in 314, Constantine remained as the sole ruler of the Roman world. He converted to Christianity, which had made its appearance during the reign of Augustus, and which, in spite of the numerous persecutions against it, had spread during the reigns of the previous emperors. At the end of the fourth century, it became the Empire’s official religion. Constantine established Byzantium as the capital, which was rebuilt in 330 and renamed Constantinople (now Istanbul). The death of Constantine (337) marked the beginning of the civil war between the rival Caesars, which continued until his only living son, Constantius II reunified the Empire. He was succeeded by Julian the Apostate, known as such because of his renunciation of Christianity, and then by Jovian (363-364).

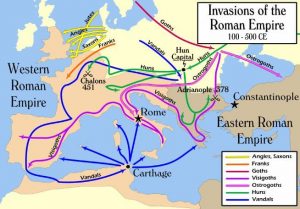

The empire then split again after the death of the Western emperor Valentinian II, and under the reign of Theodosius I, it was united for the last time. When Theodosius died (395), his two sons divided the empire: Arcadius became emperor of the East (395-408) and Honorius emperor of the West (395-423).

In the 5th century, the Western provinces of the Roman Empire were impoverished by the taxes required for the maintenance of the army and bureaucracy, as well as the civil war and the invasions of the Germanic peoples. At first, the conciliatory policy of appointing the invaders to military positions in the Roman army and administrative positions in the government was successful. However, the invading peoples from the East gradually set out to conquer the West, and at the end of the 4th century, Alaric I, the King of the Visigoths, occupied Illyria and laid waste to Greece. In 410 he conquered and sacked Rome, but he died shortly thereafter. His successor Ataulf (410-415) led the Visigoths to Gaul and in 419 the Visigothic King Wallia received permission from Emperor Honorius to settle in the southwest of Gaul, where he founded a Visigothic kingdom. Around this time the Vandals, Suebi and Alans had already invaded Hispania, so Honorius was forced to recognize the authority of these peoples in the province. During the reign of his successor, Valentinian III, the Vandals, under the command of Genseric, conquered Carthage, while Gaul and Italy were invaded by the Huns, led by Attila. He first marched on Gaul but the Visigoths, already Christianized and loyal to Rome, confronted him. In 451 an army of Romans and Visigoths, commanded by Flavius Aetius, defeated the Huns in the Battle of the Catalaunian Plains. The following year, Attila invaded Lombardy, but could not continue advancing south and died in 453. In 455, Valentinian, the last Western descendent of Theodosius, was assassinated. In the period between his death and 476 the title of emperor of the West was held by nine rulers, although the real power in the shadows was Ricimer, a Roman general of Suebian origin, also known as the ‘proclaimer of kings’. Romulus Augustulus, the last Western emperor, was deposed by Odoacer, the King of the Herules, whom his troops proclaimed King of Italy in 476. The Eastern Empire, also called the Byzantine Empire, would last until 1453.