The Church in the Middle Ages was a very powerful institution as it was a deeply religious time. For this reason, the Catholic Church had a great influence on society and, although other creeds existed, in the 11th century Europe was largely Christian.

Beyond the borders that separated the European kingdoms, a new concept of union was born: Christianity.

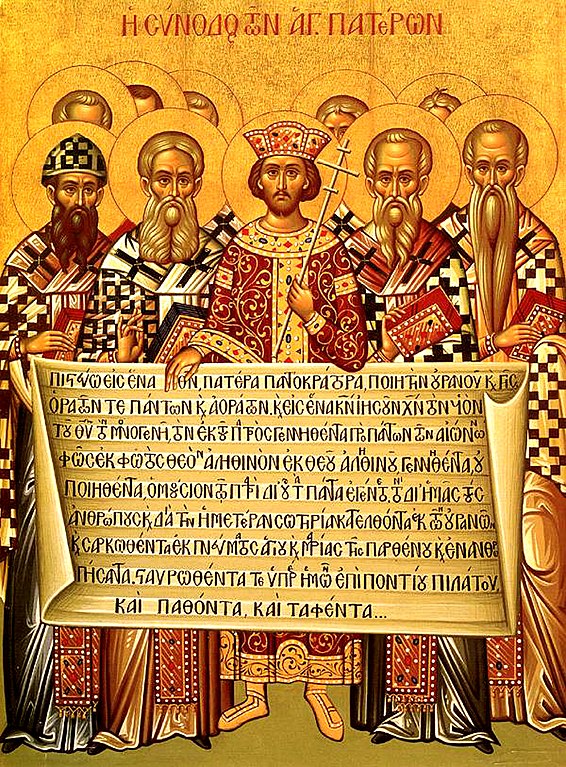

Despite these achievements, Christendom was deeply affected when, in 1054, the Byzantine bishops denied the authority of the Pope, causing the so-called Eastern schism.

Since then, the European Christian world has been divided in two: the East opted for the Greek Orthodox Church, while the West remained faithful to the Roman Catholic Church.

In the West, the Church was closely linked to feudal society; the Church itself was a great feudal power, since it owned a third of the territorial property of the Catholic world and, among other things, had the right to tithe, which was a tenth of the crops of all the people.

In addition, many members of the nobility became bishops. They received their diocese as concessions from kings or other nobles and, like any other feudal lord, had fiefdoms and numerous vassals. As a consequence of this, the Church became secularized and its customs relaxed.

Christianity and Church

Contents

About a thousand years ago almost all of Western Europe began to be called Christianity, because all its kingdoms abided by the authority of the Pope and all its inhabitants professed Christianity. All Christian territories were considered a single empire and its most important figures were the Pope and the emperor. The Church was then very powerful; bishops and abbots owned large tracts of land; the clergy, who were almost the only educated people, were in charge of educating the young, helping the poor and were the main advisers of the kings.

The other creeds

Despite the fact that in the eleventh century Western Europe was mostly Christian, there was a minority that was not: Jews and Muslims.

The Jews lived dispersed in many European cities dedicated, above all, to commerce. This religious group was not well liked. The Christians tolerated it although, on many occasions, they were persecuted for their ideas.

Since the 8th century, the Muslims occupied almost all of Spain. There they formed a very powerful group whose capital was in the city of Córdoba.

The organization of the Church in the Middle Ages

The Church in the Middle Ages had a lot of power. This was due to its enormous wealth, its clear organization and its cultural importance, which was opposed to the disorder, ignorance and violence of feudal society. All members of the Church made up the clergy, which was divided into two: the secular clergy and the regular clergy. The spiritual leader of all was the Pope.

The secular clergy

With the name of secular clergy those members of the Church who lived in the world, mixed with the laity, were designated: the Pope, the archbishops, the bishops and the parish priests.

The parish priests were in command of small districts called parishes. Several parishes formed a diocese, the head of which was a bishop, and several dioceses formed an archdiocese, headed by an archbishop.

Regular clergy

From the sixth century on, the regular clergy was organized in the West. Unlike the secular clergy, its members chose to isolate themselves from the world and live in monasteries ruled by an abbot. They also followed specific rules.

In the West, monasticism was initiated by Saint Benedict of Nursia, who founded the Benedictine order. His rule was based on the motto ora et labora, that is, pray and work. At the same time, the Benedictine order forced its members to fulfill vows of obedience, chastity, and poverty. The rule of St. Benedict was endorsed by the Papacy.

Clergy problems

In the early Middle Ages, the clergy were chosen by the religious community. From the 10th century, on the other hand, the monarchs decided to reserve that right called investiture.

In this way the clergy, deprived of all independence, was subject to the princes and lords, and at their choice could fall on characters who lacked all spiritual wealth.

This caused the loosening of customs and the two main vices of the time: simony, which consisted in the purchase of ecclesiastical offices through influence or money, and Nicolaitans, that is, the rejection of religious celibacy, transgressing the purity of ecclesiastical customs.

Despite this corruption, the clergy tried to humanize the rude customs of the time and avoid constant wars.

Due to the so-called right of asylum, it prohibited any violent act against those who were inside a church or convent. By the peace of God, he forbade the feudal lords to attack in battle those who did not fight. Finally, God’s truce consisted of the prohibition of fighting from Friday to Sunday and during religious festivities, under pain of excommunication.

Benedictine problems

The Benedictine rule, transplanted from the Monte Cassino monastery in Italy to other countries, proved to have some weak points. Since each monastery was autonomous, each one of them developed in great isolation. Furthermore, one of the requirements of the rule was the obligation of each monk to remain his whole life in a monastery in which he had entered. This rule produced a lack of contact between the monasteries and motivated the monks to be easily influenced by people who took advantage of their lack of information. According to the rule, the monks elected their abbot without the bishop being able to interfere in these elections. However, this rule was disobeyed: not only the bishops meddled in the elections, but also the laity, who offered money in exchange for the monks to choose their preferred candidate. In this way, the Benedictine order became corrupted.

Cultural centers

Life in the monasteries was perfectly regulated: people prayed and worked. However, not all monks were engaged in the same work. Some worked in the orchards, others were dedicated to artisan work, and there were some who were engaged in an eminently cultural enterprise: they copied, decorated and bound the manuscripts that contained the great works of classical knowledge. These manuscripts or codices, written with goose feathers, were adorned with polychrome miniatures (flowers, landscapes and characters) and were jealously kept in the libraries of the monasteries. The only schools of the time also functioned in the monasteries. In them the future monks and many lay people, studied the first letters.

Ecclesiastical renewal

In the eleventh century, the regular clergy reacted against the relaxation of the Church’s customs and the power of the laity over it. The monastic movement was reformed by two blessed convents.

Cluny, the spirit of reform

The first reform started with the Abbey of Cluny, founded in 910. The monks of Cluny opted for the exclusive protection of the Pope (and not that of the bishop or the feudal lord) and reinforced the authority of the abbot.

Under these reforms the Cluniac order was born, which spread rapidly in Europe. At its peak in popularity, at the beginning of the 12th century, it possessed nearly 1,500 monasteries, all of them under the authority of the Abbot of Cluny.

The Cluniac order

The Cluniac order was essentially an aristocratic order, as most of its monks were members of the nobility. Perhaps because of this, manual labor was no longer considered a suitable occupation and was replaced by an elaborate liturgy, which occupied most of the monks’ time. Cluny’s organization was based on the feudal idea of hierarchy: in the same way that in feudal society there was a king at the top, with counts, dukes, knights and the rest on a scale from high to low importance, the abbot of Cluny was the head of a whole hierarchy of subordinate members. All the Cluniac monasteries were under his authority.

Citeaux, the return to simplicity

However, in the middle of the 12th century, the Cluniacs moved away from the Benedictine ideal of life and became extremely rich. This gave rise to a second reform that started from the monastery of Citeaux, also in France; its promoter was San Bernardo de Claraval.

In search of a more secluded and strict life, the Cisternians founded their own order. The Cistercian order spread through Europe in the 13th century, and its expansion was also spectacular.

Saint Bernard of Clairvaux

The expansion and influence of the Cistercian order was due, in large part, to the activity of San Bernardo. This personage entered the abbey of Citeaux in the year 1112 and three years later, he chose a place to found a new monastery of which he was the first abbot: Clairvaux Abbey. Saint Bernard, supported by the Papacy, exerted enormous influence in fighting heresies. He was also a profound thinker and writer: he left more than 350 sermons and around 500 letters. While doing this, he ruled his abbey of 700 monks. When he died, Clairvaux Abbey had at least 68 monasteries dependent on it.

The Investiture Complaint

Thanks to the Benedictine reforms, the regular clergy became largely independent from the influence of the laity.

However, one problem remained to be solved; the election or investiture of the Pope and of the bishops who, since the 10th century, were appointed by the Emperor of the Holy German Empire.

From the 11th century, the Popes sought to put an end to this situation. For this reason, in the year 1075 Pope Gregory VII, who dreamed of a Church free from the influence of the German emperors, published a decree that prohibited all laity from investing any member of the Church including the Supreme Pontiff.

This decree originated a series of violent conflicts between the Pope and the German Emperor Henry IV called the Investiture Querella. For refusing to comply, Henry IV was excommunicated. As excommunication was the worst punishment there was, Henry IV had to humble himself before the Pope, asking forgiveness on his knees in the Italian castle of Canossa, in Italy.

This conflict ended in 1122 with the signing of the Concordat of Worms, which was agreed between Pope Callisto II and Emperor Henry V. Through the Concordat, the emperor forever renounced the appointment of bishops and popes.

From then on, the powers of the Church and the empire were defined and the Catholic Church was strengthened.

Faith in the Middle Ages

With ecclesiastical reforms, the Catholic Church achieved supreme power in the 12th century. Her triumph was also due to the wave of Christian fervor that engulfed the lower classes.

Faith was founded on the hope of a better life. The veneration of the Virgin, the saints and the relics that, it was believed, could work miracles, and spread throughout Christendom.

On the other hand, the Church guided its parishioners, preventing them from falling into heresies or false beliefs. To achieve this she had two powerful weapons: excommunication and the Inquisition.

Through excommunication, all those who did not obey its orders were expelled from the Church. The excommunicated person could not receive sacraments, and was outside the divine law. Excommunication was the worst punishment of the Middle Ages.

On the other hand, in the 12th century the Inquisition was founded: an ecclesiastical court that investigated people of doubtful faith. To obtain information, the inquisitors tortured the accused.

The punishments varied according to the sin: from riding on the back of a donkey with a rope around his neck and a pointed hat called a sanbenito to being burned at the stake.

Pilgrimages

One of the manifestations of the attachment of feudal society to religious beliefs were pilgrimages: trips that the faithful, both rich and poor, made on foot to different religious sanctuaries and that lasted months or years.

The most important pilgrimage centers were Rome, the spiritual capital of Christendom; Jerusalem, where the Holy Sepulcher was located, and Santiago de Compostela, where the Apostle Santiago was believed to be buried.

Christians went on pilgrimage for very different reasons. Some fulfilled penances or a promise, others sought purification, and others did it out of curiosity or the desire to trade in the places where the pilgrims arrived.

The Santiago guide

In the 11th century, Santiago de Compostela, in northern Spain, became as important a place of pilgrimage as Rome and Jerusalem. The pilgrimages were related in an extensive codex from the 12th century. This manuscript contained an authentic pilgrim’s guide in which the faithful were warned of the dangers of the road and at the same time, the pilgrimage to Santiago was encouraged.

Any pilgrim was subjected to the hardships of the journey and to food and safety problems. The guide pointed out the sources of water, the types of food in the different regions and even the possible risks of assault, as well as the inns, hospitals and churches that were worth visiting.

Millennialism

Another spiritual expression of the time was millennialism, that is, the belief that a thousand years after his death, Christ would return and reign on Earth for a thousand years before the Final Judgment. Millennialism greatly influenced society. Some gave up their riches to make themselves more worthy of the coming of Christ.

The poorest, on the other hand, frequently formed sects that faced violence from the Jews, the rich or the clergy, thinking that they were unworthy of the coming of Christ.

These sects, led by presumed prophets and messiahs, were the origin of many medieval things such as, for example, that of the Albingers.

Relics and heresies

One of the manifestations of medieval piety was the cult of relics; devotion to the remains of a saint, his bones or some object related to him. The chalice from which Jesus drank at the Last Supper, The Holy Grail, was one of the most sought after relics but was never found. According to the Gospel of Saint John, the Jew Joseph of Arimathea claimed the body of Christ to bury it, and also took away the Holy Grail, which over time was lost. The Holy Grail was the origin of many medieval stories, and also, of some heresies.

In the late 12th century, for example, a sect of French monks, the Albigensesm claimed to possess the Holy Grail. Then the King of France, Philip II, obtained papal consent to declare war on them for heresy.